One of the highlights of attending the International Conference on Thinking (ICOT) was the opportunity to collaborate with group of teachers in the 'Curriculum Kitchen' workshop presented by Ewan McIntosh and Kynan Robinson of NoTosh. I should have known what to expect. Any conversation with Ewan is likely to make you stop and think. NoTosh celebrates questions and is not afraid to ask the sort of difficult questions you would rather turn a blind-eye to. In this instance the post workshop evaluation left participants at this conference with one mightily significant question.

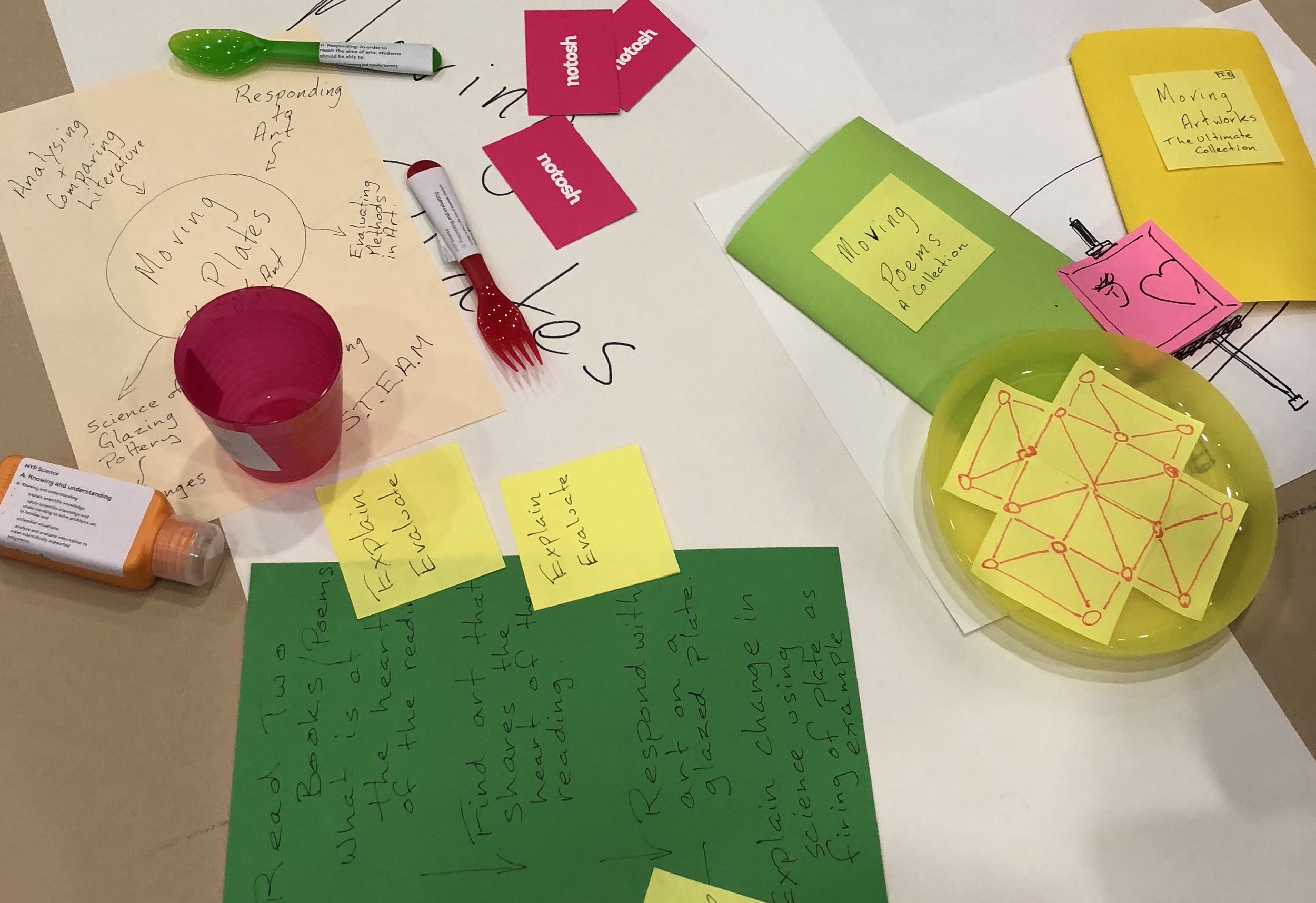

The ‘Curriculum Kitchen’ workshop uses the structures and roles of a professional kitchen and the process of planning a meal for the restaurant it serves as a metaphor for planning a unit of learning. The ingredients are elements from the required curriculum, the participants are asked to take on roles such as head chef and the conclusion is the presentation of the collaboratively planned unit. We were challenged to form groups with people we did not know and to form groups that were a diverse mix of genders, cultures and languages. I was the sole English speaker in my group but despite the language barrier we rose to the challenge and prepared a series of lessons we were proud to share.

At the conclusion of the workshop we came back together as one group and discussed the processes we had used to achieve our goals. What we learned had little to do with curriculum development but a great deal to do with how we had approached the challenge of functioning as a collaborative team working to create something new. It was at this stage that Ewan proffered the observation that left us all with this mighty question.

Despite this being a ‘thinking’ conference, despite us all being advocates for structured and scaffolded models of thinking, not one group had applied any thinking routines, utilised a collaborative planning protocol or talked about applying an inquiry model or design thinking cycle. It wasn’t that we didn’t know about them. It wasn’t that we don’t know how to use them. It wasn’t that we don’t value them. We had all the knowledge we could desire on the how to and the why of a broad set of thinking tools and anyone of these would have enhanced the process, but we did not use any of them. Why was this the case and what does this reveal about our teaching of these methods to our students?

This realisation left us with much to ponder beginning with what is the purpose of our teaching of thinking strategies. Understanding our “why” is an important first step. Clarifying “why” we teach thinking is critical if we are to make the right moves down the track. When you begin using thinking routines and protocols in your class you find that they bring a new depth to the conversations you have with your students. Thinking is hard work and it is a process that can be enhanced by the inclusion of some structure. By requiring students to use a routine you provide them with the structure they need and when used with the right stimulus you are able to both deepen their thinking and make it visible. As the thinking of your students is made visible you gain insights into their understanding and are able to make adjustments to your lessons to target gaps and meet their needs. In this sense thinking routines, protocols and models of inquiry are excellent tools for enhancing student learning of skills and content. If this is our purpose and then we might not mind that a group of thinking experts choose not to use any of these tools, after all they are merely teaching tools and it is the role of the teacher to select the most appropriate tool.

The trouble is that few of us would argue that thinking routines and the like are merely pedagogical moves to be applied only in the context of a thinking classroom. Our aim is to have our students develop an understanding of the value that these tools bring to their learning, their thinking and their problem solving beyond the walls of the classroom. We would hope that experience with these tools in our classrooms would result in our students adopting the use of these tools independently. Our goal might be to produce life-long learners capable of self-regulating their application of strategies for efficient and effective thinking; but we seemed to be evidence that knowledge of these methods and even valuing them, is not sufficient.

When you analyse a typical classroom it is quickly apparent that the teacher plays the part of the ringmaster. The learning that occurs is for the most part a consequence of the decisions that the teacher makes. To be certain the learner always has the most important role to play in determining the true outcomes that they achieve as consequence of the experience but the context for the learning is set by the decisions made by the teacher. The what and the how of the learning is set by the teacher and students then engage (or not) in the experiences presented to them. In the typical thinking classroom, this extends to the choice of thinking strategies hopefully as a result of the teacher’s identification of the types of thinking required. With an understanding of the thinking they wish to make routine for their students and armed with a selection of thinking routines that will enable this, the teacher invites the students to join them in the process of making meaning.

What we want is a situation where the students are able to move into the role played by the teacher in the above process. We hope that as a result of regular exposure to this process of learning through the use of thinking routines that our students will be able to self-select the type of thinking required in particular context and then choose a thinking-tool that will meet their needs. If such a process works, we should see this pattern of behavior in adults when problem-solving individually and as adults but the reality is that we don’t. Ask the average person or survey a group of people as they make daily decisions of any scale and they typically do not describe their use of what we may consider a thinking routine. Why might this be?

Is it that thinking routines are relevant to the sort of problem solving and thinking required in the classroom but are not useful in the real world? This is a notion that should seem flawed to teachers who see learning within schools as preparation for so much more than an exit exam. Our aim is to not just fill our students heads with the knowledge they need but to develop in them the dispositions and capabilities they will require to thrive in the world beyond school based learning. We routinely talk about bringing real world learning into our classrooms. From the alternate perspective we can also see how our thinking in this “real world”, the thinking we do as adults leading normal lives can benefit from the application of some thinking routines. Consider the thinking required when making a significant purchase and the factors which determine our ultimate choice. In most cases, we might agree that the application of even a very simple strategy such as a plus/minus chart would at least allow us to see the true benefits of one selection over another, even if our final decision is guided by our hearts. Thinking is after all hard work and we often don’t do it well.

Group dynamics might have a part to play in the use of thinking routines within self-regulating groups. It is typical to see groups move through stages as they form, storm and norm. In the opening phase group dynamics are shaped by polite interactions, efforts to read the terrain of the group and to understand who fits where. Roles are not clear and there can be a reluctance to impose structure upon the group. If the group is diving straight into the task of understanding a problem the opportunity to apply a thinking routine to this process can be missed and replaced by a form of bumbling ideation where possible solutions are shared and politely discussed in a most unstructured manner. In the classroom, this bumbling disorder is avoided as a result of teacher intervention. We do not typically hand our students a problem, leave them to form groups and come back an hour later to see what solutions might have evolved. Structure of some form is imposed upon the group even if it is quite minimal.

This points to the need to teach our students not only to value thinking and the use of thinking tools as strategies to enhance the quality of their thinking, but of the need to teach them how to both select thinking routines based on their awareness of the thinking they require and the capacity to integrate these methods into the collaborative process. The learning experience that we had in the ‘Curriculum Kitchen’ is one model for how this sort of learning might be facilitated. The brief we were given was very open. There was some structure imposed but it was minimal and we had scope to make our own ways towards the destination. At the conclusion of the task time was dedicated to reflection on the processes we had used and our teachers played an important role in asking us questions which guided our thinking and helped us develop an understanding of what we had done. In a traditional reading of the workshop model by this stage the lesson was over, in reality it was only now that the learning began. The implication is that when we plan lessons we need to allocate much more time to the process of reflection as it is at this stage of the lesson that we are able to discuss the choices that were made and to evaluate the strategies deployed or ignored.

Some of our teaching time needs to be dedicated to the task of teaching our students how to collaborate, how to form a group, structure a group, provide leadership for a group and manage the complexities of the groups social dynamics all while achieving the group’s goals and purposes. Doing so requires all of our best teaching moves including modelling, direct instruction, guided and independent practice, with meaningful and transformative assessment that is both external (teacher & peer) and internal (self). Group work is a frequently used strategy in schools but when looked at closely we must question if it is serving purposes other than a division of labour. Collaboration is one of the most commonly referenced 21st Century Skills but successful collaboration is challenging and something that many adults struggle with as evidenced by the large selection of management books and courses which focus on developing the capacity to lead high-perfoming teams. Our students need to learn these skills while at school and then develop the capacity to apply their knowledge when participating in collaborative teams without a teacher providing the external management.

Harvard’s Project Zero asks us to consider a triadic-dispositions where there is the required capacity, the necessary motivation and a sensitivity to the utility of particular set of behaviours. When it comes to strategic-thinking and with that the adoption of thinking moves, our aim needs to be thusly elaborated. Our students need to value the use of thinking strategies, understand when such moves are useful and have the desire to utilise them but this is not enough. Building on from having established a disposition to utilise a thinking strategy they must also have the social capacity to bring these tools into their collaborative circles. Their needs to be a social valuing of thinking and thinking routines as tools to achieve the purpose of the collaborative group. We need to educate not only individuals to value thinking but to develop a collective awareness of the value of our collective application of thinking strategies.

Edward P Clapp shared his research on ‘Participatory Creativity’ at ICOT. He argues that creativity is not the result of the thinking of the lone genius but a consequence of the thinking of many. Edward encourages us to move from worshiping the individual thinker to an appreciation of the collective intelligence that is revealed when we explore the biography of an idea. While Edward’s work is focused on the participatory nature of creativity, it can be readily applied to thinking in it broadest forms and points us towards an understanding that as all thinking is social we need to be teaching our students to maximise the benefits of their thinking within social groups. This opens the door to a pedagogy that not only recognises, as Vygotsky argues, that learning occurs within social contexts and through the individual’s participation in societies but one that seeks to educate the collective mind.

By Nigel Coutts

Related - Initial Reflection on ICOT 2018

Read more:

Clapp, E. (2017) Participatory creativity: Introducing access and equity to the creative classroom. New York: Routledge

D. N. Perkins, Eileen Jay, and Shari Tishman (1993) Beyond Abilities: A Dispositional Theory of Thinking Harvard University

Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard university press.