After two days of talking about curriculum, integration, STEM, STEAM and HASS I am left with more questions than I started with. In some respects, the concept of curriculum integration is simple. It is after all something that Primary teachers almost take for granted. But for Senior and Tertiary educators the question of curriculum integration is inherently complex. At all levels questions emerge of what curriculum integration might achieve, what purposes it serves, what it could and should look like and how it should be supported by curriculum planners. In the current climate, with its debate around the role of education within an innovation economy, shaped by technology and confronting demands for a STEAM enabled workforce the shape of our curriculum is under pressure. This article doesn’t hope to answer these questions but to stimulate discussion.

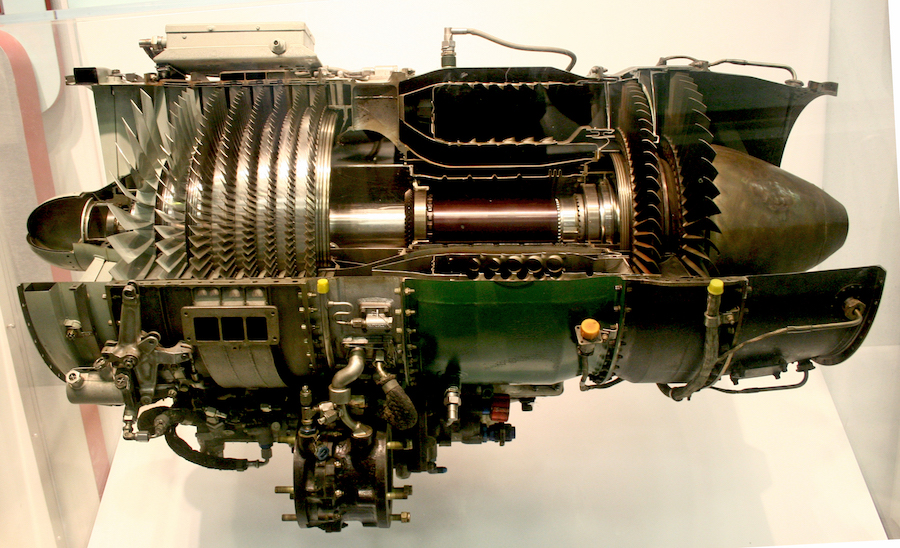

The current curriculum model across schools and tertiary institutions has its origins deep in humanities historic structuring of knowledge. While in large part a product of the industrial revolution and the adoption of an assembly line approach the subject/discipline model emerged out of the need for specialisation of knowledge. Travel back to the times of Da Vinci and perhaps the world was a different place. The great philosopher, artist, engineer, mathematician, scientists dabbled with the knowing and the doing of diverse disciplines. Specialisation had not taken hold of our structuring of knowledge as it has today where even within a single department of a university it is quite likely that two professors working mere metres from each other will have much in their respective fields of expertise that does not overlap. This structuring of knowledge in conjunction with age based advancement and classes of students paired with a teacher gives shape to our modern classroom.

This model of disciplines has profound influence on the shape of our educational institutions. It gives the organisational structure of departments, is embodied in a divided curriculum, is evident in the timetables and teacher specialisations. It produces silos in which teachers work and students learn. It forces students to make choices around their patterns of study, influences career aspirations and ultimately confines our immediate post school options. Increasingly it is this model which is under attack and proponents of STEM and STEAM are at the forefront of the battle for an integrated curriculum. But what should this integrated curriculum look like and why might it be desirable.

Understanding the “Why?” of curriculum is a valid first step but there are no clear answers. Seemingly the simplest rationale for curriculum integration is that can be a more efficient approach. Schools are always time poor and the curriculums fullness makes the division of this time into discrete blocks inefficient. Curriculum integration can allow learning in one discipline to directly support learning in another. Student learning time is maximised if their writing lesson supports their learning in science and connects with the content that they must cover for mathematics. This is the rationale often cited in primary schools but it is one that carries less weight in senior schools. Departmental structures, budgets, timetabling constraints and teacher specialisations all act against integration even for the sake of economy, after all if I am a time poor maths teacher why would I want to give some of my lesson time over to language arts? Integration for the sake of efficient time use within a crowded curriculum leaves one wondering why the curriculum is so crowded that it relies upon integration to make it teachable, but that is another topic.

Another reason for curriculum integration is based on the quality of learning that it is seen to produce. Transfer of knowledge across disciplines is viewed as a valuable goal but a difficult one within strict discipline based learning environments. Integration reveals the connections between content, skills, dispositions and importantly concepts across disciplines. Teachers will decry their pupils inability to apply a skill or concept acquired in one subject to another and yet fail to see that the distinct segregation of learning contributes to this. Integration is the perceived remedy to this. This linking of knowledge processing approaches, is often described as a critical disposition for an innovation economy where students will be required to bring together many divergent threads to create new opportunities for wealth and quality living: a particularly strong component of the STEAM perspective.

There are those who argue that integration is a required approach if education is to produce a workforce ready for this era of innovation and disruptive technologies. More than knowledge students will require broad skills often described as the four Cs of creativity, collaboration, communication and critical thinking with compassion or empathy sometimes added as a fifth essential element. Building a strong knowledge base within the classic disciplines is considered of lesser importance to the ability to act with what one knows to solve emerging and discovered problems. In times where the problems that we confront cut across the boundaries of disciplines students need to be able to use a diversity of approaches and a broad knowledge base towards new solutions. This is made additionally complex where knowledge itself is seen no longer as a commodity and the ability to learn, unlearn and relearn is as Alvin Toffler describes the dominant quality of the new literate class. For those working with the Australian Curriculum who support these notions the “General Capabilities” could be the Trojan horse which makes this possible according to Prof. Alan Reid.

Models of integration abound from simple combinations to total immersion. Debate about the specifics of each term continues and while of interest to academics may not serve the wider purposes of the debate. One way of looking at the way we shall integrate is to look at the degree of integration which occurs. At the simplest level are those opportunities for students to apply learning from one discipline alongside learning in another. Each discipline retains its unique flavour and presence but the integration is visible. At the most complex or complete level of integration students seamlessly draw on the knowledge and methods of the disciplines to explore broad concepts or solve problems. At this level of integration there are significant implications to the structuring of the students’ learning and their experience of schooling. Implications abound for timetabling and in senior school settings departmental structures. While a generalist primary teacher may be confident across multiple disciplines and deliver programmes which draw on diverse skill and knowledge sets this becomes increasingly complex and demanding as we move into senior school. Finding time for collaboration in schools is sufficiently challenging without the need for collaborations across departments and timetable streams.

Project Based Learning is often seen as one method of integrating the curriculum. Done well it can allow students to develop their inquiry and problem solving skills. Used with the right problems, that are considered important to the learners it can be highly motivating and produce a love of learning. Used as a way to have students “discover” content or answers that the teacher clearly already knows, it adds little value. Used in conjunction with traditional assessment methods which value the recall of specific facts or learned moves it can have a negative impact on achievement scores compared to direct instruction where students are told the information they are required to know for the test. Project Based Learning is best seen as the independent practice of the methods for using what we know and can do to solve meaningful problems and of the learning moves we will continue to use beyond school.

The other question of why should we integrate the curriculum is, in part more a question of what should the new disciplines of learning be. If we move towards STEAM does this replace the disciplines of which it is composed. Does the next generation curriculum have a STEAM curriculum or do we continue with distinct curriculum areas and rely on teachers to identify the opportunities for integrations? If we move to STEAM or STEM do we have a complimentary field of HASS that combines Humanities and Social Sciences or Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences? Countless alternate acronyms rapidly emerge as each group of educators seeks to reimagine the curriculum of the future while ensuring their area of speciality retains or adopts a prominent position.

This is where the bigger questions emerge. What part should the traditional disciplines play in the future of education? Are we approaching a time where they may no longer serve our needs? Are there better or more relevant ways of organising knowledge than is made possible with the existing disciplines? Is the growing trend towards curriculum integration a sign that now is the time to remove the silos that the disciplines create? In some respects, these may be the wrong questions to be asking? Perhaps we need to go back a step and look at the knowledge processing moves which we rely upon within the disciplines and across the disciplines.

Show a group of professionals a scene and they will each see something different. In part this difference is a result of the frames they have become immersed in as a result of their choice of discipline. A geographer will see patterns of lands use, a biologist will see signs of life an economist will see potential loss centres and so on. Each looks at the world with particular frames and within each discipline there are a multitude of frames which shape our perception and make possible a particular set of responses. These frames have value and access to a broad set of frames, made possible through collaborations or other means is likely to lead to more creative solutions to the problems we encounter. This is closely associated to the common call to add Arts to the mix of STEM as a way to bring an alternate “creative” perspective to the problems encountered.

What if we seek to maintain the unique frames of the disciplines but do away with the silos that they create? What if we have a set of frames that capture all of the ways that humanity approaches the task of knowledge processing and then draw upon the best mix of frames for the situation at hand? What if each individual as a consequence of their schooling was made aware of the affordances of each frame and could select the right mix of frames for the unique situation they are confronted by? How would this model allow for better solutions to emerge and for different understandings and conclusions to be drawn which are not possible when we only have access to the frames of a discipline?

Something to ponder, as I started with I don’t have answers only questions and wonderings.

By Nigel Coutts