The past two weeks, I have considered some of the consequences of a world where uncertainty and unpredictable change is the norm. These are “postnormal times” as Sardar describes “Ours is a transitional age, a time without the confidence that we can return to any past we have known and with no confidence in any path to a desirable, attainable or sustainable future.” (Sardar, 2010) There once was a predictable pattern to change; things became predictably larger or smaller, more or less frequent, quicker and easier, swung to the left or swung to the right. Now, this is not the case. Change is fundamental, and the solutions which worked for us in the past, such as our reliance on technology, science and due processes for politics and social understandings are no longer adequate.

In response to this, industry is identifying new skill sets which are considered necessary in these times of uncertainty. Skills such as active learning and learning strategies should be the core business of schools. After all, the fundamental business of education systems from the customers perspective is learning. We often get this the wrong way around and focus on what the teacher does and as such, consider the core business of schools to be teaching. This is like a restaurant that focuses on what the chefs do, cooking, and forget about the experience of the customer, which is dining and the practice of being a diner. If schools get it right, our teachers will do excellent teaching that creates the right opportunities for our students to become learners. Our collective ability to learn and by doing so, adapt to changing circumstances through the acquisition of new skills and dispositions is what Edward de Bono refers to as EBNE; Essential But Not Enough.

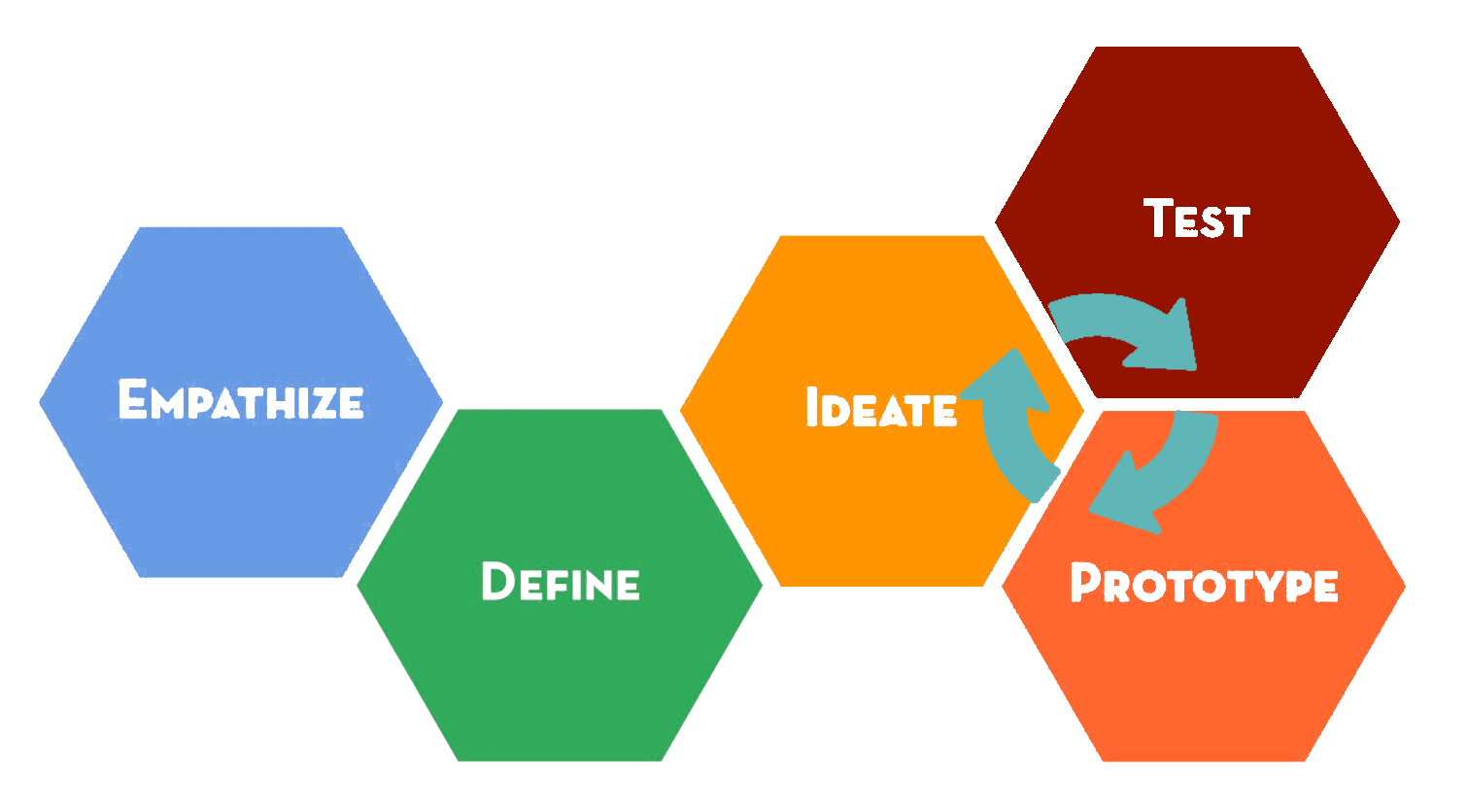

The capacity to learn new skills in response to rapid changes is EBNE because in doing, we become dependent upon others to identify and solve the emerging problem for us. Learning in a traditional sense relies upon someone else possessing knowledge and skills that we hope to acquire. According to Daniel Wilson, this model works for traditional problems, even quite complicated ones which are the norm in large systems. Someone somewhere will have experienced this problem before, and there is a solution that is proven to work. The challenge is to identify the problem, find the corresponding solution and apply it in ways that are respectful of context.

But uncertainty means that the challenges we confront have not been experienced before. These complex problems combine challenges from the past with new challenges and new contexts. We can not rely on wisdom from elsewhere as the knowledge we require does not yet exist. We are the first to confront the particular challenges, and we are the first with access to the opportunities that come from solving these in ways which are most responsive to modern times. Learning to learn in these times is, therefore, EBNE, but what then do we need.

Creativity becomes the key path towards solutions to the challenges of uncertainty. According to Tim Brown, past CEO of the design innovation company IDEO creativity is the greatest weapon we have against uncertainty.

“One of the greatest weapons that we have against uncertainty is creativity. It’s how we forge something new out of it.” - Tim Brown IDEO

Creativity is what will allow us to look at the world and see opportunity amidst the chaos of uncertainty. Creativity offers us the fresh perspectives we need, guides us towards new questions and allows novel solutions to emerge. Truly successful individuals will be those who see the world as a place to be interpreted through a creative lens. They will seek out fresh perspectives and challenge the status quo. Organisations will empower their creative individuals by enabling collective and participatory creativity where innovative solutions emerge from truly collaborative processes of ideation.

“The problems of today are too big for one person or organisation to solve alone. We need many people bringing a vast diversity of perspectives to begin to think about old challenges in new ways." - Tim Brown IDEO

Commonly, creativity is seen as a disposition which some people possess and others do not. We see it as a process for individuals and point to the works of those we imagine to be creative geniuses as examples of this process in action. Such an individualistic definition of creativity does not serve us well in times of wide-scale uncertainty. In these postnormal times, no individual will possess all of the information necessary to understand fully and subsequently respond to challenges defined by their complex nature. A more collaborative definition of creativity might better serve our purposes.

Inner Circle - Expertise is the path to solving complicated problems

Outer Circle - Emergence is the path to solving complex problems

Source: Daniel Wilson - @danielwilsonPZ

This is what Edward Clapp describes in his book “Participatory Creativity”. In this, creativity is defined as:

“Creativity is a distributed process of idea development that takes place over time and incorporates the contributions of a diverse network of actors, each of whom uniquely participate in the development of ideas in various ways.” - Edward P. Clapp - Participatory Creativity

Such a definition encourages us to see creativity not as the thinking of an individual but as the output of many. Successful organisations will be those that create the conditions which encourage participatory creativity at all levels. The most successful organisations will be those who nurture opportunities for participatory creativity, both internally and externally. Organisations which are closed shops, where ideas are secreted away, where collaboration is curtailed will confront uncertainty through a restrictive lens where alternate possibilities and perspectives remain unseen.

“At IDEO, we’ve worked hard to shift our mindset around uncertainty to one of curiosity and excitement. We value embracing ambiguity—finding the opportunity in the grey space between your comfort zone and the next big idea.” - Tim Brown IDEO

This is the ultimate challenge for schools. Teaching our students to be creative participants is vital for their success, but this too is EBNE. Until schools become places that genuinely encourage models of participatory creativity for every member of their community they will remain doomed to repeat the practices from our past and continue to be surprised when the results thusly achieved do not change.

By Nigel Coutts