We all understand that creativity is an important skill for the future and we want our students to leave our classrooms with what David & Tom Kelley of IDEO call creative confidence. A quick read of the introductory chapter of any book on the future of the workplace will reveal an emphasis on the importance of creativity for individual and organisational success. As one of the four or alternatively five Cs (the others are critical thinking/reflection, collaboration, communication and often compassion) creativity is part of a skill set that differentiates human capacities from those readily replaced by automation and artificial intelligence. The difficulty with creativity is it is not easy and perhaps thanks to our experience of schooling not a natural attribute of many adults. What creativity needs is a process and/or a structure that allows us to bring our intellect to the development of creative solutions.

While we often refer to the need to think outside the box, as Ewan Macintosh of ‘NoTosh’ points out, we need the box when it provides the just necessary structure to scaffold our thinking. The more creative we need to be the more we need some structure to keep us on track. For educators, there are other reasons to provide a process to scaffold creativity. Asking our students to ‘be more creative’ without some scaffold is a strategy doomed to fail. If our goal is to keep our students within a zone of proximal development as defined by Lev Vygotsky, then we need to provide a scaffold that will take their capacity for creative problem-solving to a level beyond where they currently are and where they can only achieve success with appropriate scaffolding. Further when we seek to assess creativity and offer feedback on what has been achieved and feed-forward on where the learner can go next we need a process against which we can track progress. To only assess the end product will leave the students with little guidance as to how they may enhance their next effort. Without a process, students are left to be continually guessing at how they should approach the next challenge.

Finding this process was the focus of a workshop offered by University of Newcastle, Sydney as part of Vivid Ideas. Led by John Scott participants were introduced to five approaches to creativity which can be readily used with teams to enhance the results of their creative endeavours. Each offers a process that can be applied to a variety of problems and a common language that can be used within teams as they learn together.

The first invites team members to state and restate the problem. A seemingly simple step but one that encourages a full understanding of the problem and encourages seeing it from alternative perspectives. Restating the problem is an excellent check of understanding and will often reveal a better approach towards a solution. Strategies such as rephrasing the problem using positive instead of negative terms, identifying persuasive or opinionated words or drawing a picture or diagram of the problem were suggested.

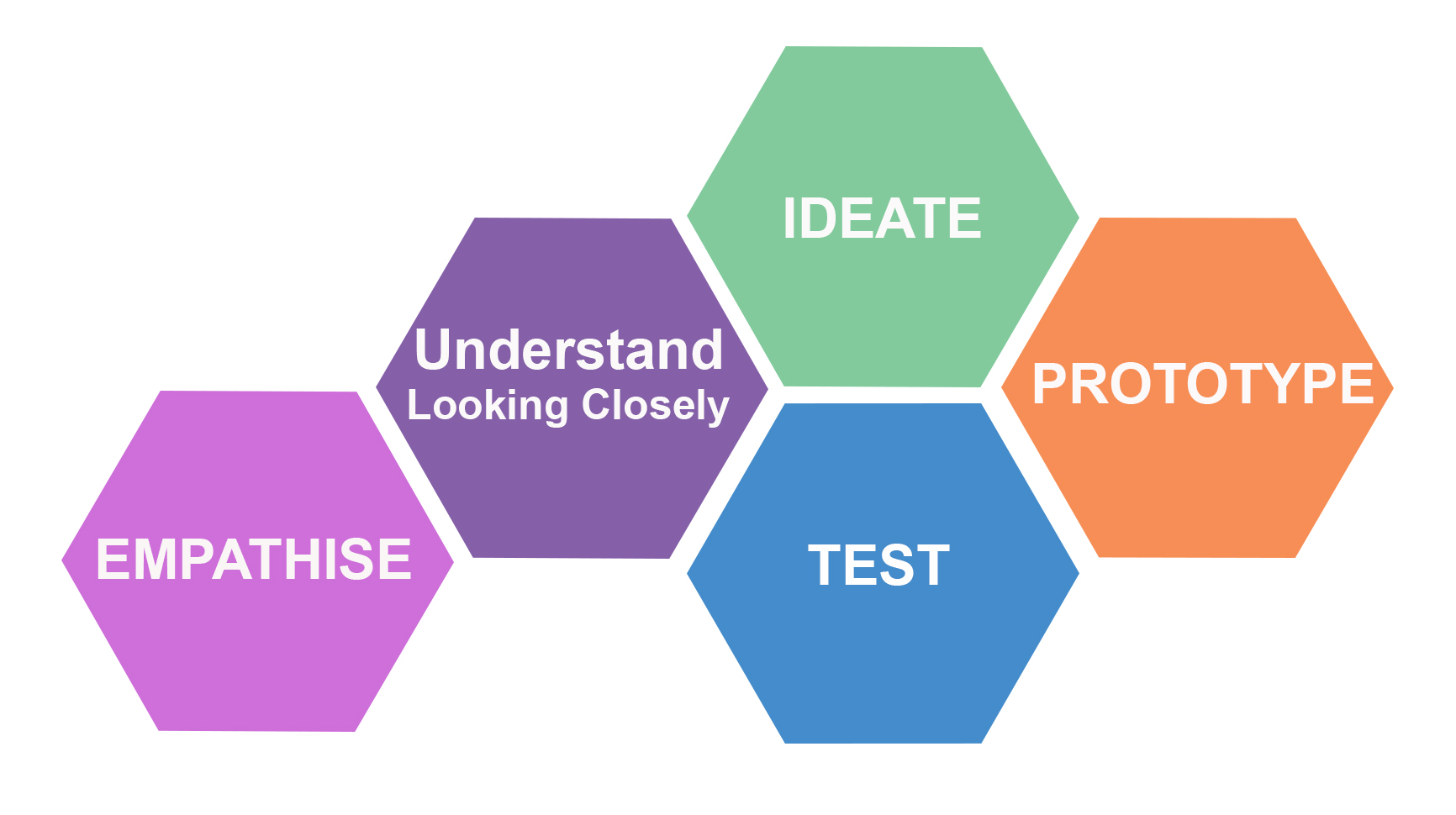

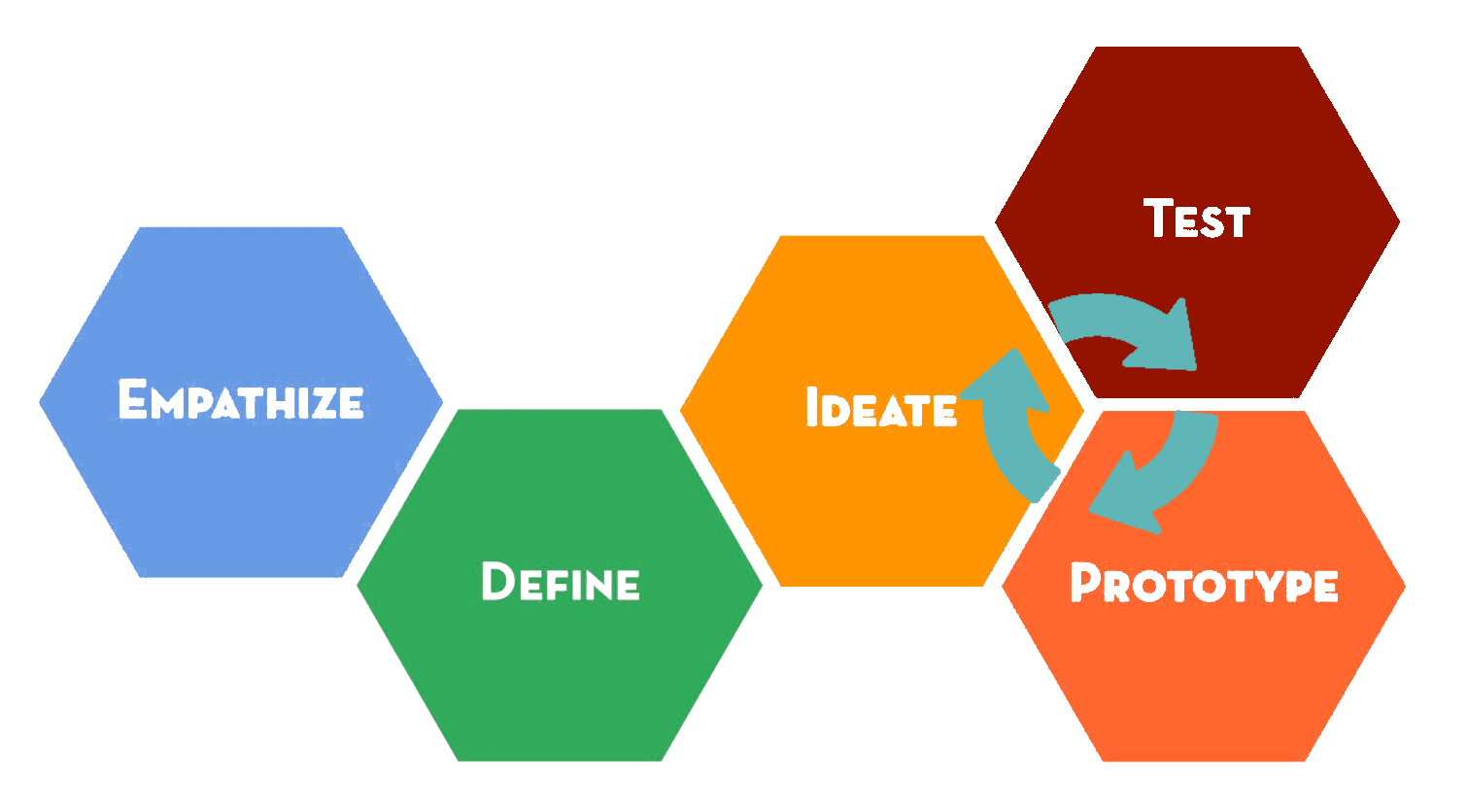

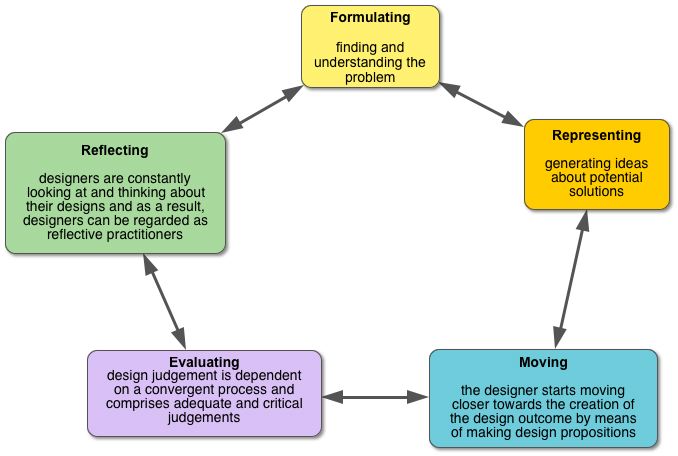

A model of design thinking modified from the IDEO d.School model

Design Thinking was offered as a solution to complex problems where a highly iterative process is useful. Design thinking is becoming increasingly popular in schools and is even being included in state and national curriculums. It is a process which has been explored elsewhere on this site and there are many models which might be adapted to suit an organisation or a particular problem. Perhaps the key understanding is that it is a process which is based on experimentation and rapid prototyping. For it to be successfully embraced by organisations there must be a culture that is tolerant of failure as without this playful ideation and iteration will not occur.

This model of design thinking has been successful with Year Two students

Agile and Lean processes were explored as possible processes. Agile brings a process focused on user stories and a rapid process for responding. Agile is very much problem solving by doing and with each cycle producing a ‘done’ component of the larger solution it allows for rapid progress. Having identified a user story, self-organising teams enter a ‘sprint’ to identify and implement the first part of the solution or response. Individuals opt into what is called a ‘scrum’ which is the core unit of a ‘sprint’ based on their desire to play a part in that part of the solution. Lean is about identifying and removing waste and continuous improvement. By understanding what is there and always looking for ways to improve what is done, teams can develop enhanced products and operations. A key ingredient in ‘Lean’ is respect for the the perspective and problems confronting every stakeholder. Part of the strategy is understanding how processes and systems impact individuals and groups and then taking appropriate actions.

The final approach is the use of Edward de Bono’s thinker hats. The 'Six Thinking Hats’ are a common element in classrooms and it was interesting to see this methodology being shared with a mixed audience. It would be interesting to see the hats being worn in the executive suite of a large corporation. Each hat asks the wearer to engage with a different mode of thinking. White hat thinkers are analytical and interested in facts, figures and information. Red hat thinking is about emotion and feeling, the Black hat is critical and full of judgement. Yellow hat thinking is positive and seeks to explain why an idea will work and the benefits it brings. Green hats bring alternatives and Blue hats look at the big picture and bring a reflective, metacognitive approach to the overall process; an understanding of how the creative process is unfolding and what type of thinking it might require more of. The Six Hat process works best when each hat is given a voice and understanding the value that each hat brings to an individual’s or team’s thinking encourages this. It should not be a process of labelling the thinking style most commonly adopted by a team member but a way to bring new thinking modes into their repertoire.

With an understanding of a set of processes for creativity the team and individual should be better able to approach complex challenges. As mastery of the methods is developed new opportunities can be created by blending elements of one approach with another. Knowing when to break the rules comes with experience and maturity and allows the right approach to be matched to the context. In seeking to maximise the creativity of individuals and teams perhaps the most critical element is a willingness to embrace failure. There is no method guaranteed to produce desirable results the first time but a culture that punishes failure will always limit its creative potential.