For all of us, learning was an innate part of life. It was something we just did, that was as natural to us as breathing. If not for this innate desire to learn and with it the ability to do so, we would never learn to walk, or speak or interact with others.

But at some point learning stops being something we do and becomes more like something that happens to us. Our initial self-drive to learn is replaced by learning as a part of our life that is highly regulated, controlled, monitored and externalised. For some people this compartmentalisation of our lives with learning as a self contained piece that takes place inside of schools results in the belief that it is something we can opt out of.

Learning becomes the ability to absorb and make use of information and skills that are presented to us in a manner that another person or group of people decides is best. Learning becomes something we do in a specific place and at a specific time, for a set number of years and via a lockstep sequence with a group of peers sharing a common age.

From this model of learning comes a string of consequences. It separates learning from the control of the individual, it places the decision making process about learning priorities into the hands of others and it dictates what is and is not success. It divides us into people who are skilled at learning and those who are not skilled at it according to this model and subsequently for the first time it forces us to evaluate our ability to learn. This assessment of our ability to learn and indeed our ability in general is placed into the hands of others and this assessment of us by others for many plays a critical role in determining our self worth.

All of this does not stop learning from happening outside this controlled environment. Children continue to play games, to learn from their peers, to discover ideas for themselves, but this model does separate and devalue this learning from the supposedly real learning that occurs in schools.

Many have written and spoken about the current education paradigm as being modeled around the needs of the industrial revolution; that schools are modeled after factories with students entering as raw product, teachers performing the routine labour of transferring information and skills and adults leaving at the other end as product ready for the needs of the industry. It is also well documented that the world we once prepared children for no longer exists. Through a mix of economic forces, changing priorities, technological change and globalisation our children will leave school requiring a different skill set marked by an ability to creatively identify opportunities and develop creative solutions to capitalise on these. In his book ‘Creating Innovators’ Tony Wagner describes the mindset and orientation of an individual prepared for this world. He identifies what is required to be an innovator as ‘some of the qualities of innovators that I now understand as essential such as perseverance, a willingness to experiment, take calculated risks, and tolerate failure, and the capacity for design thinking, in addition to critical thinking.’ These are not skills developed through even the most judicious application of a ‘chalk and talk’ methodology which while less prevalent today remains a common pedagogy. A similar set of skills required of the innovator is offered by Tim Brown CEO of IDEO writing for Harvard Business Review and cited by Tony Wagner, is ‘empathy, integrative thinking (the ability to see all the salient and sometimes contradictory aspects of a problem), optimism, experimentalism and collaboration. Tim states that ‘My experience is that many people outside professional design have a natural aptitude for design thinking, which the right developmentand experiences can unlock.’ Sir Ken Robinson’s often cited comment on creativity and education reveals his beliefs on why there are not more people leaving school equipped with the skills of the innovator: ‘I believe this passionately: that we don't grow into creativity, we grow out of it. Or rather, we get educated out if it’.

Through a series of interviews with successful innovators Tony Wagner describes the forces and people that shaped them and influenced their development. In most cases these influencers fell outside of the normal systems of school and college, educators and mentors described as ‘outliers’ by Tony, educators who despite the system, manage to encourage young innovators to follow their passion and seek out challenges that matter.

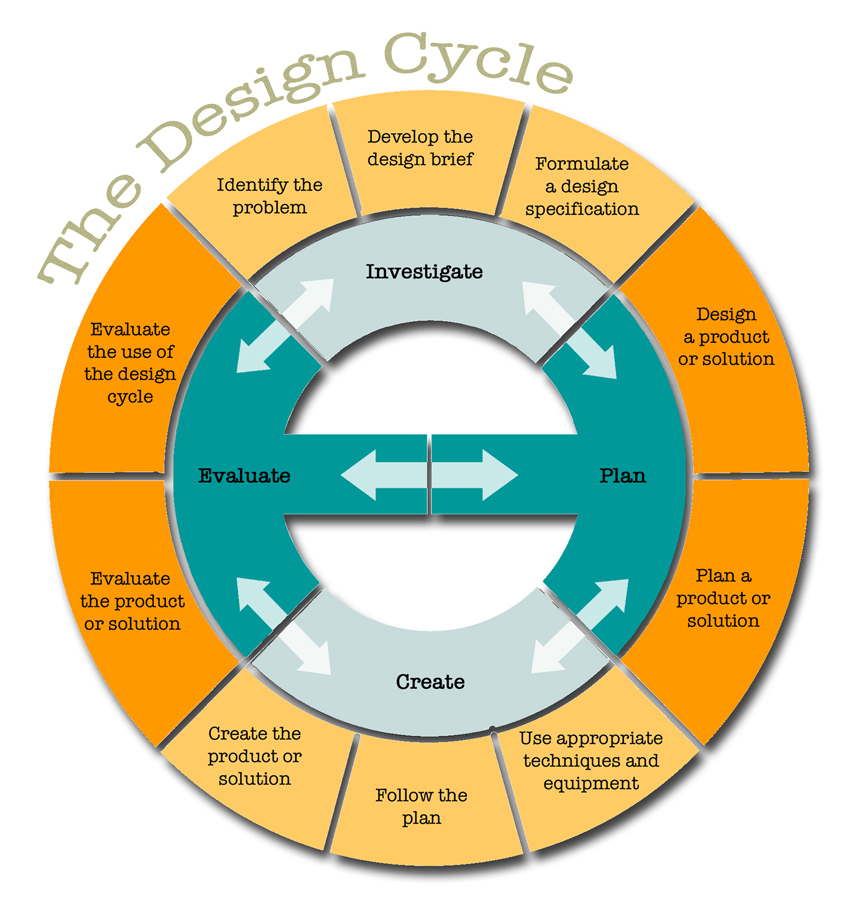

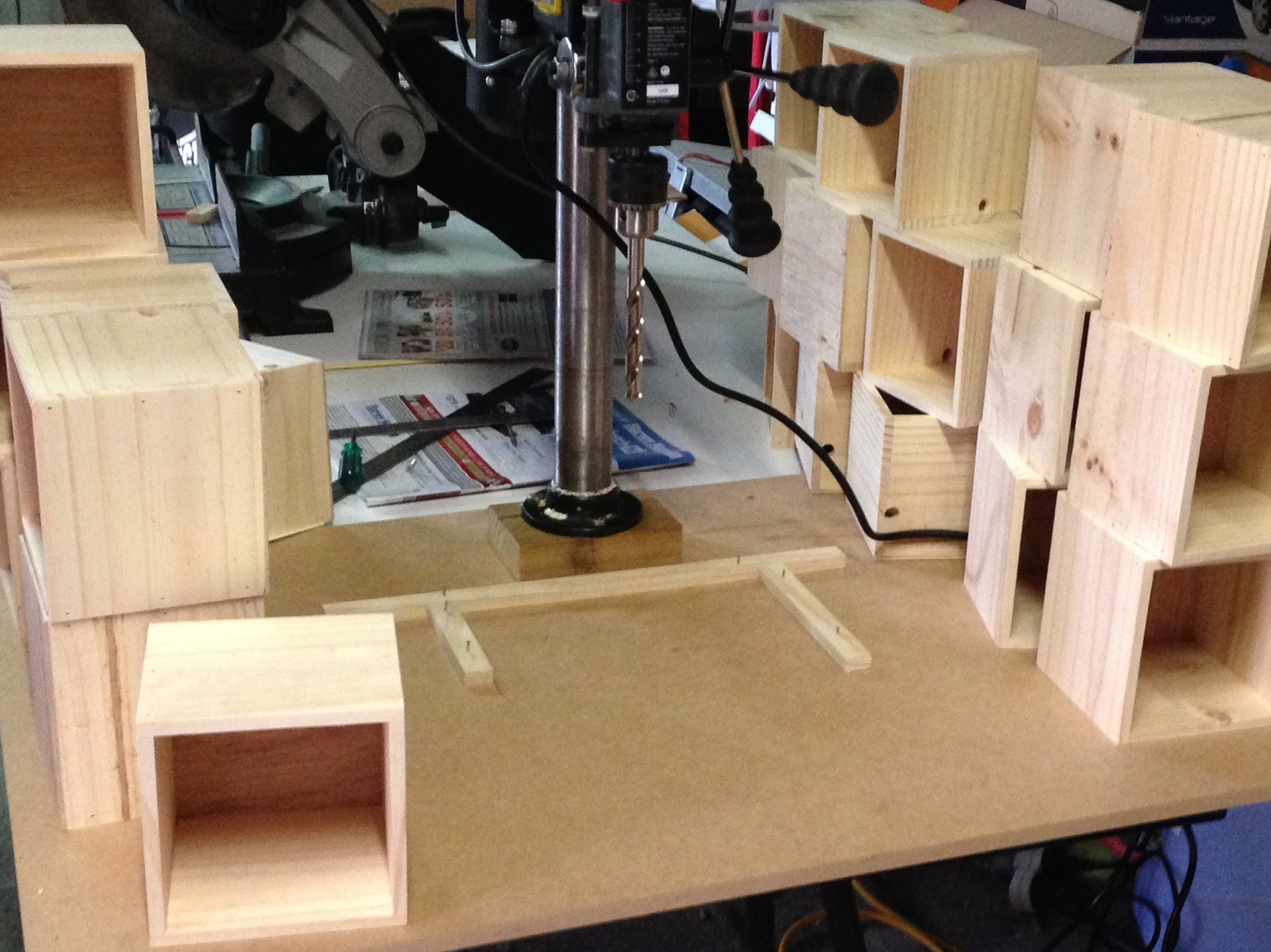

Ian Jukes is another educator calling for change to educational systems. At ‘Edutech’ in Brisbane last year, he described the disappearance from western nations of careers based upon routine cognitive tasks, the traditional office jobs which are so easily relocated to countries with cheap labour. Tony Wagner echoes this ‘A growing number of our good-paying blue-collar and even white-collar jobs are now being done in other countries that have increasingly well-educated and far-less-expensive labour forces’. Ian calls for an educational paradigm through which students develop an ability to learn, unlearn, and relearn and to do so rapidly. Students leave this system not with a pool of knowledge but with what Ian calls ‘Headware skills’ creative skills that are rapidly adaptable and within the control of the individual. Ian calls for educational systems to not just shift teachings to new ideas delivered in the same mode but for a shift in the focus towards providing opportunities for students to become creative problem finders and solvers. As an example a school may identify the emerging App economy and desire to teach students this new skill but this does not mean we teach app design in the same way we taught grammar, the skills needed now will be outmoded by next year or sooner, we need to teach the mindset required for app design; a problem solving, design process with inquiry skills and the ability to quickly learn and unlearn skills to suit the needs of the task.

To meet these challenges and to ensure the learner is at the centre of the learning with a voice and opportunities to self-assess and self-direct, schools need to change focus. Ian describes two sets of skills, short life and long life. Short life skills are the ones that quickly become redundant or outdated. Long life skills are creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, problem solving and social intelligence and have value to the individual even as circumstances change. These are the skills schools need to develop but these skills will not develop in a system where the teacher is a content delivery mechanism.

They may be developed in a system that embraces Sugata Mitra’s view of learning as an 'edge of chaos phenomenon'. In this, the individual is provided with opportunities to discover and solve problems that matter but in allowing learners to imagine the problems, the control and organisation loved by too many schools is lost. Only by understanding that the value of these experiences lies in the life long skills that students will apply and experience and by not focusing on the content lessons missed as a result of the chaos will schools truly prepare their students for the tomorrow that already exists just outside their classrooms. When schools do this, maybe learning will remain an innate and natural part of ones life.

By Nigel Coutts