Sometimes, it seems the class you are teaching is more than you can cope with.

A whole range of factors seem to conspire against you at the start of the year and despite your efforts you don’t feel you are gaining the usual traction with your students. Whether it’s the particular mix of learners, the specific learning needs of some students or the challenging behaviour of others, things are not quite going as planned and you are starting to question your ability as a teacher and maybe even thinking now is the time to switch careers.

The truth is all teachers face times like this. The sad part is that many good teachers decide that the best move for them in these times is to leave the profession; a trend we need to fix.

It is easy to imagine that the mark of a competent teacher is their ability to successfully manage the learning needs of any group of students or the needs of any specific student purely as a result of their individual talents. Such thinking is deeply flawed but is reinforced by organisational structures that isolate teachers and privatise the teaching process. When we become more open and collaborative we see that we are not alone in our struggles to meet the needs of our students. Opportunities to share stories from the classroom, allow us to see that even the teachers we imagine as the most talented and experienced have moments where they are challenged by the learning needs of their students, have trouble connecting with individuals and confront feelings of self-doubt.

Collaborative teams of teachers and specialists are essential and should be the norm in all schools. A collaborative planning team allows teachers to formally discuss the learning needs of their students as individuals and as members of a learning community. A diverse collaborative team will bring new perspectives and understandings of the challenges and offer alternate strategies for meeting the needs of the learners. An effective collaborative team will be supportive of the teacher and ensure that the teacher is well supported. While the ultimate goal of the team is to develop a strategy that serves the needs of the learner, the first task is to ensure the teacher is looked after and knows that the team is supporting their efforts.

Membership of the collaborative team will vary depending on the specifics of the situation but should always include the child’s parents or carers. The perspective that the child’s family brings is important to any plans made for the child and their participation in the plans implementation is vital. In schools that achieve the greatest success for their students, close ties will already exist with the parent body and discussions about the learning goals of the school and the part that families can play in supporting these will be the norm.

Access to relevant professional development should be the norm and teachers should be able to tailor their access to this based on the needs of their learners. This professional development should include access to professionals such as child psychologists, occupational therapists and counsellors who have knowledge of the specific circumstances of the child and the context of their learning. Access to such specialists can be expensive and a goal of developing a more equitable education system should include providing access to these professional services for all who require it.

Believing in the growth potential of every student is critical to success. By knowing where our students are with their learning, seeking to understand how they learn and the obstacles that might impede their learning teachers can set achievable goals and map a path towards these. Knowing that the path will take many twists and turns and times progress might seem slow is part of the process. Teachers with a true growth mindset will know that there are aspects of teaching that trigger their fixed mindset and that the same applies for their students. By working and learning together it is possible to see growth as an achievable goal and from that point it becomes possible to make progress in the desired direction.

As individual teachers and as teaching teams it is important that we look after ourselves in addition to looking after the needs of our students. When we find ourselves with a challenging student or class the workload and stress escalates and as it does our capacity to problem solve diminishes. We need to understand that before we can meet the needs of our students we need to meet our personal needs. Taking the personal time to rest, reset and reflect is critical, as is time with our families and time away from thinking about work. Setting clear boundaries, disconnecting from work by turing off email and engaging with our personal interests are habits that make us better teachers.

The teacher that our students need, is the teacher who is willing to do what it takes to meet their needs but who is not willing to sacrifice their own sanity in doing so. Great teachers know their limits and know that the best way to meet the needs of their learners is by building a collaborative team around them. Great teachers seek help, ask for guidance and understand that they cannot know all the answers. They are gentle on themselves and forgiving of mistakes, recognising that every day is a new day with new hope and fresh possibility.

By Nigel Coutts

Happy Daze Booths and Suno Stool courtesy of BFX - Node Chair/Desk courtesy Steelcase

Getting creative with our learning spaces

Learning is impacted by many forces such as the learner’s disposition to the process, the quality of their teacher’s pedagogy, their emotional state and nature of the curriculum. Amongst this long list of factors is naturally the environment in which that learning occurs and the relationship between the environment and the learner. Our understanding of this relationship has grown and fortunately today’s educators are more willing to experiment with the way spaces are organised to promote learning.

Looking online you easily find a whole range of beautifully furnished learning spaces. Rather than a single, one-size fits all arrangement these spaces create zones designed to meet the particular learning needs of those using the space. Using metaphors from ancient civilisations spaces are seen as Campfires, Watering Holes or Cave Spaces; each serving a different purpose but acting together to meet the needs of a group of learners throughout a day. Campfires are spaces that allow communication on a large scale and fit the model of the lecture into a friendlier space that encourages more back and forth interaction. The Campfire space is best supported by spaces for collaboration on a smaller scale with nearby breakout spaces or flexibility in furnishings that offer this function. Watering Holes are spaces for small group collaboration and should include spaces that facilitate spontaneous interactions and socialisation. By nature, they are likely to be loud but can be adapted to the specific needs of the group. Cave Spaces are for individuals and pairs who need access to a quiet space for reflection and meditative thinking.

These books will inspire your learning space design.

Unfortunately, we are not all blessed with expansive classrooms which can readily accommodate a diversity of learning zones. The challenge becomes one of creatively using the space and furnishings you have to create flexible spaces. A good example of this can be found in one of our smallest classrooms.

Located on the top floor of the historically listed Parkes Building, 3B is a class of happy and confident students led by a teacher Emma, who was prepared to give up a teachers desk to give more space back to her learners. For the students Year Three marks an important milestone in their education as they transition from Prep into Junior School. Through the careful arrangement of desks, book cases, cushions and the addition of a playful tee-pee (a feature of some of our Prep Classrooms), Emma was able to welcome her class into a space that was designed to meet their learning needs while being a delightful and welcoming space. Within a small room Emma has created that highly prized mix of campfire, watering hole and cave space. As students settle into the space Emma plans to hand ownership over to the students and will work with them to create spaces that best suit their needs. In this way Emma is providing her students with opportunities for metacognition as they reflect on what works best for them as learners.

Emma is not alone in using the space she has creatively. Last year we were able to purchase a range of new furnishings. Looking to break the mould and explore alternate models for furnishing learning space they explored what was available and what might suit the limited space available. The result is a mix of comfortable lounges which can be arranged to form partly enclosed booths, round tables with writeable surfaces to encourage collaboration and desks at heights to accommodate standing, kneeling or sitting on the floor. Some of the furniture being explored is 'movement permissible’ and is designed to allow students a degree of wiggle room that is reported as enhancing focus for some learners. Long days of sitting in hard plastic chairs does little to assist anyone’s focus but a little comfort and the possibility to shift your weight can overcome some of the obstacles to learning that arise out of environmental factors.

A recent addition to the mix is a set of combination chair and desk. Similar in form to the desks we might recall from university lecture halls, the modern version accommodates learning with ample desk space, storage under the chair and wheels to allow a speedy reconfiguration of the room. Students are able to quickly form small groups, and then shift again to share their learning with another set of learners while taking all they need with them. The smaller footprint and ease of movement of these desk and chair combinations allows a large open floor space to be easily created to facilitate learning that requires additional room.

A tradition of the primary classroom is the use of under desk storage. This feature ensures students have what they need close by and keeps the classroom neat but can equally restrict options as students feel they belong to the one space in the room where their belongings are stored. Under desk storage is perhaps a remnant of the educations history where students would typically have a large pile of exercise books, text books, novels and a multitude of pencil cases to hold all of their stationery needs. With much of this now replaced by electronic devices less space is needed and by doing away with under desks we have created a more dynamic learning space.

The key here is that we are actively thinking about the connections between the learning and thinking we hope to make routine and the physical environment in which it occurs. Rather than being directed by our experience of school we are considering what the environment might be like and how that may best support our goals.

by Nigel Coutts

Related:

A culture of innovation requires trust and resilience

"A person who never made a mistake never tried anything new”

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

Albert Einstein

Two quotes by Albert Einstein point to the importance of creating a culture within our schools (and organisations) that encourages experimentation, innovation, tinkering and indeed failure. If we are serious about embracing change, exploring new approaches, maximising the possibilities of new technologies, applying lessons from new research and truly seek to prepare our students for a new work order, we must become organisations that encourage learning from failure.

There is an easy way to avoid mistakes and with the classroom remaining a largely private domain it is easily done. Rather than trying new ideas and sharing the results with your colleagues, maintain the status quo, hide any mistakes and avoid risky situations where your ideas might be challenged. Don’t volunteer for projects, don’t share new strategies and don’t ask for help when you are unsure of what to do. In many organisations, doing so will allow you to avoid critical feedback and ensure you many long and peaceful days.

The danger in such an approach is that you are locking yourself away from any opportunity for growth and restricting the opportunities available to your students. By not sharing you limit the potential benefits of your innovative ideas to the students you teach and by not asking for help you limit the scope of possible solutions to those you might imagine. What hope will your students have of developing a growth mindset or desire to try new ideas if they never see their teacher doing the same.

The alternative is to try new ideas, in public, while asking for help and seeking feedback.

Often your ideas will be criticised. Sometimes they will be misunderstood. Sometimes people will be critical of you. Often your ideas will fail, or be blocked, or ignored. There will be times when you want to hide and there will be times when you want to give up. More importantly there will be times when your idea makes a genuine difference. There will be times when your idea meets the ideas of another and together they grow into something you had never imagined. Through the feedback you receive, from the critical comments, from the questions and by learning from your blunders you will find that your ideas can make a real difference. While it is true that the more ideas you share, the more criticism you face; it is also true that the more ideas you share, the more success you have.

Being or becoming an innovator within an organisation requires a high-degree of resilience. The innovator must genuinely embrace the belief that ideas are better when they are shared. Innovators know and believe that the surest path to a truly innovative solution is to share that idea early in its development so that it might benefit from the wisdom of many minds. But for this to happen those receiving the idea must adopt a mindset of possibility. Too often our first response to a new idea is to find and share all the reasons why it won’t work or at least won’t work here. Rather than starting with “This won’t work because . . .” we need to flip our thinking and respond “This might work if we . . .”.

If schools and organisations wish to activate the innovators in their mix they must learn to celebrate the mistakes and missteps along the way. In biology the word ‘culture’ is used to describe a medium that promotes growth; a culture medium. When we embrace this idea and apply it to the culture of our schools we can see that the right culture creates the conditions necessary for growth. Innovation will only thrive in a culture where the individual feels safe to try new ideas.

The challenge for schools in creating a culture that is accepting of failure is that the messaging of this is conveyed as much in the little things as in the public affirmations of a desire to innovate. The tone of an email, the subtle reprimand, the abrupt response to a question that shuts down the conversation are all factors which restrict innovation. Genuine encouragement of innovative ideas will see individuals and teams praised for the ideas that do not work as much as they are praised for the ones that do.

I feel lucky to work an environment that encourages innovation and I have seen time and time again ideas that I have shared become better and stronger thanks to the input of many minds. Those who do not work in such an environment need to find ways to innovate within their context. Maybe innovations occurs within a small team. Maybe you share your ideas with a few trusted colleagues before sharing them with the whole school. Sometimes you need to try that new idea in private, gathering evidence of its utility as you do before you share it with a wider audience. Making connections with educators in other schools and other countries via social media can provide you with the support and sounding-board your ideas need. It may not be an easy path, and may often seem a lonely one, but your students deserve it, and so do you.

By Nigel Coutts

Change and why we all see it differently

Change is the background noise of the modern workplace. The constant force that winds its way into all we do. Thanks to forces such as technology, globalisation, ever expanding communication networks and global warming, living with change has become almost normal. At the forefront of our response to change lies education. If the young people of today are to thrive beyond the walls of the classroom they will need to be able to cope with a world characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. The children of todays Kindergarten will enter the workplace in the fourth-decade of the 21st Century. We debate the merits of teaching 21st Century Skills and what they might be while teaching children who have lived their entire lives in that very century.

Increasingly the message from those who are hiring and educating young adults, from those analysing the demands of work and life in contemporary times is that education needs to change and change rapidly. In Australia, the Foundation for Young Australians has produced multiple reports that detail the skills and dispositions children will need. In the United States, multiple research projects point to a workforce that will require more preparation, higher social or analytical skills and where continuous training is the norm. (See Pew Research) On a global level the OECD has presented their ‘Future of Work’ report and share that

‘Globalisation, technological progress and demographic change are having a profound impact on OECD labour markets, affecting both the quantity and quality of jobs that are available, as well as how and by whom they are carried out. The future of work offers unparalleled opportunities, but there are also significant challenges associated with these mega-trends.’

Other changes to the shape of work and life in the coming years result from ongoing trends in artificial intelligence, automation and the rise of the ‘gig’ economy where freelance and short term contract work is common and training and retraining for new projects is the norm. In this economy, it is more important to be able to learn than it is to be learned.

What is very clear is that change is not going away. The challenge is how will schools and individual teachers respond to this drive for urgent change.

How we respond to change varies immensely. From experience with driving change and from conversations and observations with individuals as they approach change in various forms it seems that there are broad typologies which emerge along a continuum from those who actively seek to change to those who actively resist it.

There are those for whom change is the next adventure. They are happy to embrace change and are likely to be strong advocates for it. These are either the initiators or first followers of change. For the leader seeking to implement change in an organisation this group at first make things easy and during the early phases of a change initiative you might wish everyone was as adventurous as these happy folk. The trouble is however rapid the pace of change it will not be sufficient for those who love change almost for change’s sake. They will quickly grow frustrated and while the advocate for change they may do so in a manner that ostracises others. They are also likely to move on to the next new thing just as quickly as they jumped on board with the last and as a result no change is ever fully implemented. The great idea they embrace today will be tomorrow’s old thing and while the revel in the journey everyone else gets ‘change fatigue’.

There are those who are open to change but need to be shown the evidence. They ask questions, seek clarification, engage in research of their own and challenge assumptions. They can seem difficult at times and even appear adversarial but when you understand their motivation and feed them the information they desire they are likely to become some of your strongest supporters (at least amongst others like them). These are the ones who will want the full version of the report. Who will read the twenty page document outlining the change and then ask for copies of the referenced research papers. The quick and dirty snapshot is likely to get this group off side and they will complain about a lack of detail.

There are those who need to be show how the change will impact them. They want the human side of the story and while this group also craves details they do not need charts and data but stories of how the change will be ‘felt’ within the organisation. In schools much of their focus will be on how the change will effect the students but they will also want to know about the impact it might have on their colleagues. Will this create more work, will there be time to adjust, will there be support, who will this change impact. This group are likely to look at the real world impact of the change and are likely to back their concerns with ‘tales from the coal-face’. Show them the human face of the change and how it will make their lives better and they will get on board. Smothering them with data and jargon is likely to make them suspicious.

There are also those who just want to be told what to do. They don’t really buy into the change; they don’t resist it either. They are not impressed by the research or the stories of how this will change their lives for the better. They want the snapshot version and the chance to get on with what they have to do. This group might make the process of change easy to implement but they are not likely to help you win supporters who don’t have a similar mindset and the more subtle elements of complex change will be entirely lost to them.

There are those who publicly embrace the change but in the privacy of the classroom continue as they have always done. These are the ones who have seen change come and go and have learned that by keeping their head down they can wait out this new initiative. Some will believe that they have indeed adopted the change but the reality is that do not fully understand it. Others will believe that the new idea is precisely what they have always done and again they are not understanding the new approach. Deprivatising education has many advantages including sharing best practices, enhancing collegiality and promoting collaboration; it also makes visible those who passively resist change.

There are those who are outright afraid of change. These are often the ones who are the most outspoken advocates of the status quo. They are likely to attack those initiating the change and will claim that it is too complicated, has been poorly articulated and is ill conceived. They may not have strong arguments for why things should stay as they are and they are not likely to be persuaded by reason. Once you recognise that the reaction you are seeing is driven by fear you can start to address the real issues for this group. This is a group that will definitely require one to one time and who need to see that the change is manageable. They are more likely to be persuaded to give new ideas a go by their close peers than by management. When they do come around they are likely to bring others with them.

In schools, emotion and culture are linked and change of culture frequently invokes an emotional response. “A person’s sense of identity is partly determined by his or her values, which can mesh or clash with organizational values” (Smollan & Sayers 2009 p439) When cultural change is sought in a school and it is not viewed as fitting with one’s values or it calls those values into question emotional responses such as fear, anger or sadness are common.

There are of course also those for whom the change is just wrong. They understand it, they have looked at the research, listened to the rhetoric and don’t buy any of it. As author of “Good to Great”, Jim Collins might note, these are the people who have found themselves on the wrong bus and in the wrong seats. They are likely to be great people and given the right context could do great things but if they cannot find a way to align their core beliefs with the organisations vision for change they are unlikely to be truly happy. If you are leading people like this, you might find ‘Radical Candor’ by Kim Scott illuminating. Helping people find the right place, the place where they fit is the best service we can provide those who are on the wrong bus. If you are feeling like you are on the wrong bus it might be time to read Simon Sinek’s ‘Start with Why’ and explore how doing so can help you find meaning within an organisation or point you in the right direction.

Change is always complicated. A the least it involves people, personalities, cultures, beliefs, values, emotions and identity. Change initiatives have a habit of failing and do so even when all the right steps seem to have been made. Chaos theory loves change inside complex organisations and schools are indeed complex enough to ensure the results of change efforts will be unpredictable. If we at least seek to understand the motivations and perspectives of those involved in the change, we have a chance of making the right moves.

By Nigel Coutts

Scott, K. (2017) Radical Candor: How to be a great boss without losing your humanity. Macmillan: UK

Sinek, S. (2011) Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. Portfolio Penguin: London

Smollan, R & Sayers, J. (2009) Organizational Culture, Change and Emotions: A Qualitative Study, Journal of Change Management, 9:4, 435-457

Foundation for Young Australians

Deloitte - Futures of Work

Key findings about the American workforce and the changing job market

Good to Great - Article by Jim Collins

Starting the year on the right foot

Across Australia students are returning to school. Armed with fresh stationery, new books full of promise, shoes that are not yet comfortable and uniforms washed and ready to go, students will be heading off for the first day of a new year. What do they hope to find and how might we make sure their first day back sets them up for a successful year of learning?

Above all else our students will want to know that school is a safe place where they can be themselves. Students will not take risks with their learning, engage in creative thinking, adopt a growth mindset or demonstrate grit and determination if they do not feel safe. A safe and welcoming school climate is one that embraces diversity in all its forms, is forgiving of mistakes and missteps, focuses on growth and sees learning as an iterative process. When we take the time to get to know our students, when we show that we want to hear their story, discover their interests and join with them on the learning journey that lies ahead we show our students that they are what matter most. Great teachers know their students well and use that knowledge just as they use their knowledge of curriculum and pedagogy to construct the right culture for every child's learning.

A teacher I worked with for many years would begin the term by writing each member of her class a welcome note. What made this practise special was the great care with which each note was written. As the students arrived in her class at the start of the year and the start of each term they would find their personalised note waiting on their desk. Each note was carefully crafted to show that the child was known and that their teacher was happy to have them as a member of her class. The notes shared with the child their teacher’s hopes for them in the weeks and months that lay ahead and her confidence in their ability to handle the challenges they would encounter. With this strong foundation, the first hours of the school year were dedicated to building connections and celebrating the rich diversity that the students bring to the class as a result of their backgrounds, interests, strengths and weaknesses. The time spent in these opening hours established a class that put empathy and compassion before all else.

The start of the year is the perfect time to establish a culture of thinking in our classrooms. When we value thinking, make time for it to occur, ask open ended questions that permit it and when we set the clear expectation that thinking is essential in our classrooms we build a culture that advances learning. Many teachers start the year with stories of holiday adventures but fewer begin with stories of holiday thinking and learning. This can be the perfect opportunity to model your thinking as a teacher and as a life-long learner. By sharing with our students, the learning, problem solving, thinking and wondering we engage with we become the models of life-long learning they need.

“What makes you say that?” is a powerful question and one of the Ten Things that Ron Ritchhart recommends we say to our students every day. It can be a confronting question and some learners who have not been exposed to it may see it as negative feedback. It is worth explaining to the class early on that “What makes you say that?” (or the abbreviated WMYST) is a question you will ask often not because their response is flawed but because you value the thinking that led to it. WMYST is one way to take your students beyond right and wrong answers and to move the routine of the classroom away from what Dylan Wiliam calls “ping pong” questioning where the teacher asks a question, a student answers and the pattern repeats. WMYST opens up a richer dialogue where there are multiple perspectives and students are expected to reason with evidence. Establishing an expectation that students will articulate the thinking behind their responses early on brings the advantage that before long students will automatically extend their responses with the addition “and what makes me say that is . . .”.

This is also the time to set up the conditions required to enable a “growth mindset”. Being clear from day one that this year will be full of challenges and that students will have many times when they do not immediately achieve success. Failure will be a part of their learning and is a necessary requirement for true personal growth. If we reimagine failure as a part of the learning process, as a way of finding out what doesn’t work and of exploring just beyond our personal limit, it stops being a barrier and is transformed as a hurdle on the road to success. Building on this, teachers need to be clear that they value personal growth more than right answers or high test scores. The students who take responsible risks, challenge themselves, look for what they can learn from every experience and who want to be shown where they might improve are the ones who will achieve the most.

Our recently appointed Australian of the Year, Professor Michelle Yvonne Simmons captured many of these ideas beautifully in her acceptance speech, words that will undoubtedly be shared by many teachers at the start of this year. "I’ve really lived by four mantras - do what is hard, place high expectations on yourself, take risks and do something that matters” Now is the time for us to establish a culture of learning in our classrooms that allow our students to do the same. The little things we do now, the time we spend building our classroom culture, sets us up for the great year of learning we all hope for.

By Nigel Coutts

10 Things to say to your students everyday by Ron Ritchhart

Developing and Maintaining a Growth Mindset

Becoming Learners: Making time for OUR Learning

At the heart of all that we do as teachers lies the act of learning. Our hope is that our actions inspire our students to engage in a process that results in their acquisition of new knowledge, mastery of new skills and the development of capacities and dispositions which will prepare them for life beyond our classrooms. Increasingly our focus is on developing the skills and dispositions our students require to become life-long learners. We recognise that in a rapidly changing world, the capacity to take charge of your personal learning journey, to become self-navigating learners is essential.

"The fullest representations of humanity show people to be curious, vital, and self-motivated. At their best, they are agentic and inspired, striving to learn; extend themselves; master new skills; and apply their talents responsibly. (Ryan & Deci. 2000)

The challenge for teachers is to recognise the value of their personal learning for themselves, for their schools as learning organisations and for their students. Setting aside time for regular personal learning is vital for our professional growth. It is something that some of our most successful entrepreneurs recognise. Michael Simmons has researched the practices of people such as Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Oprah Winfrey, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg. He found that each of these people can attribute some of their ongoing success to their regular engagement with deliberate learning. Michael refers to this focused, consistent pattern of learning as the “five hour rule” in which individuals dedicate at least an hour of each working day to their personal learning.

For busy teachers finding five hour each week to focus on our learning is a challenge, after all we have up to thirty learners in our classes who require our attention and every day it seems that our to do list expands. To change this, we need to change our thinking and understand that the time we spend on our personal learning is time that will ultimately enhance and enrich the learning environment we provide our students. This is a strategic thinking move that takes us away from what Stephen Covey refers to as “Fire-fighting” where our day is consumed with items which are important and urgent or “Distractions" which demand our attention but are ultimately not-important for our strategic direction. By deliberate action we are able to set aside time in our schedule for the important task of developing our own capacities.

An easy way to start a learning journey is to set aside time for personal reading. There is an ever-expanding selection of books directly relevant to our role as teachers and I have shared such lists previously. If our goal is to expand our thinking then there is great value in exploring ideas outside of the immediate field of teaching and learning.

With this goal in mind here is a short list of books from outside of the field of education which are bound to get you thinking.

Post-Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back by Matthew d'Ancona

In this book, British journalist Matthew d’Ancona presents the argument that we are living in a ‘post-truth’ era where we are accepting and tolerant of lies and reluctant to accept the wisdom of experts. It is a book that might help you understand the current political climate and one that will encourage you to re-think how we prepare our students to be sceptical analysers of information and opinion. This is a book you will want to share and one you will soon be citing in conversations.

Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking by Susan Cain

We are a society that celebrates extroversion and outward displays of confidence and flamboyance but in doing so we ignore and devalue the strength of our introverts. In the classroom, our introverts go easily unnoticed. They consume less of our time and in class conversations seem to have less to contribute than their more extroverted peers. When you read “Quiet” your assumptions about introverts will be challenged and you will see the introverted people in your life through a new lens. For those who are introverts this book will help you better understand your strengths and help you handle life in a world that seems to focus on extroversion.

Find Your Why: A Practical Guide for Discovering Purpose for You and Your Team by Simon Sinek

With his best-selling book “Start with Why” Simon Sinek started a movement committed to understanding why we do what we do. In this new book Simon and his team share the strategies they have used as they help individuals and teams find their why. If you are a fan of Simon Sinek’s ideas and are looking for your why, this book is a must read.

Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond by Gene Kranz

Gene Kranz is one of those amazing individuals who has played a critical role behind the scenes of some of the defining moments of modern times. For anyone with an interest in engineering, science, space exploration or who grew up marvelling at the adventures of astronauts this book is a must-read. Gene Kranz is perhaps best known for the role he played in the safe return of the Apollo 13 astronauts as depicted in the Ron Howard film where Gene was portrayed by Ed Harris. Gene tells the story of NASA through the eyes of insider beginning in the early days of the Mercury to flights beyond the Apollo programme. An inspiring read.

Introducing Chaos: A Graphic Guide by Ziauddin Sardar, Iwona Abrams

Chaos theory is one of those ideas that we may have all heard of but few of us truly understand. In this book, the authors provide a gentle introduction to the field of chaos theory through a mix of accessible text and supporting images. If you feel that things are increasingly becoming complex and characterised by times of chaotic change, this book is the place to start an exploration of what chaos theory has to offer. A book full of insights.

and for something completely different . .

507 Mechanical Movements: Mechanisms and Devices by Henry T. Brown

This is a delightful book and one that anyone with an interest in engineering and how things work will treasure. It is full of images of simple and relatively complex mechanical arrangements. The sort of book that would have been an essential reference items for engineers at the dawn of the 20th Century when it was originally published. If you are exploring maker centred learning this book is bound to provide fresh ideas and could inspire a novel solution to a mechanical problem.

By Nigel Coutts

Related:

Good Reads for Great Assessment

Suggested Readings to Inspire Teaching

Taking the time to think

Time is the most precious of resources.

It seems that we never have enough of it and the result is a feeling of constant pressure to do things quickly. As a result, we fall into a pattern of making quick decisions, with incomplete information and then proceed to take hasty action and seek short cuts. Our busy lives, the business of those around us, the schedules we set ourselves and the constant stream of distractions and interruptions ensure we have very little time to do things well and we never seem to get things done.

"Could it be though that the disruptive, 24/ 7, multi-channel communications we value so much are actually eroding our ability to think clearly, creatively and expansively?” (Lewis, 2016 p1)

Against this trend towards doing more, in less time and at a faster pace is a trend towards slowing down, taking time and giving our minds time to catch up.

Once we realise that as described by Chris Lewis we are moving too fast to think, we can start looking for an alternate course of action. The obvious answer is to slow down, to pause, switch off and take the time we need to reset but doing this requires deliberate action. We begin the process by recognising that taking our time, slowing down and being deliberate in the processes of thinking is a pathway towards becoming more productive, more creative and more attuned to the world around us. In what seems like a contradiction in terms, the best strategy for coping with the rapid pace of our lives is not to speed up but to slow down.

Slow Looking by Shari Tishman

In “Slow Looking” by Shari Tishman the reader finds an approach to slowing doing and taking the time needed to appreciate the finer details in the world around us.

"Slow looking is a healthy response to complexity because it creates a space for the multiple dimensions of things to be perceived and appreciated. But it is a response that, while rooted in natural instinct, requires intention to sustain."

For educators, the practice of slow looking will align well with strategies from the Visible Thinking movement. If you have used strategies such as “Looking Ten Times Two” or “Look and Look Again” you have experienced slow looking. By deploying strategies which require us to switch modes and adopt a more contemplative stance backed by deliberate efforts to notice things on multiple levels, we open our minds to new possibilities. When you use these strategies with your class you will notice a new depth of thinking emerge from your students. The initial conversation may well disappoint. Surface level thinking and seeing is ingrained and takes time and persistence to overcome. As the students begin to look more closely, to see more detail and notice more of the stimulus they are engaging with a change emerges. Gradually the students embrace the opportunity that slow looking offers.

The Red Tree by Shaun Tan

"The Red Tree" by Shaun Tan is a beautiful piece of creative work by a master of the picture book genre. Each page has multiple layers of detail and meaning. It is a book that deserves time and slow looking. In a unit aimed at Year Six students we invite students to immerse themselves in this text. We begin the exploration of selected pages using the slow looking strategy of “Looking Ten Times Two”. In this strategy students are invited to look at an image quietly for at least thirty seconds allowing their eyes to wander before they stop and list ten words or phrases about any aspect of the image. The process then repeats and can indeed repeat again. With each new looking more detail emerges. The students deliberately look for details they did not notice at the first looking. After two rounds of slow looking we invite the students to share their observations. As each student shares their notes, fresh ideas emerge and the discussion takes on a life of its own. Soon students are not just discussing what they saw in the image but are asking questions about the artist’s choices, the meaning of the image and their personal take-aways.

The strategies of slow looking are not restricted to the visual. Consider looking as a synonym for perceiving and you see its potential across multiple disciplines. Tishman provides numerous examples of “slow looking” in disciplines away from those most immediately associated with the visual and through senses other than our eyes. Consider the place of “slow looking” in science as an essential strategy for noticing what is taking place in an experiment or field observation. In music “slow looking” will allow the listener to notice subtle nuances in a piece and in literature “slow looking” encourages the reader to enjoy the language moves made by the author while the practice of slow looking is a valuable tool for the author to employ as they build descriptions.

'Slow Looking' is a highly recommended strategy and those looking to implement this in their classrooms or in their own lives should begin by reading Tishman’s book.

By Nigel Coutts

Lewis, C. (2016) Too fast to think: How to reclaim your creativity in a hyper-connected work culture. Kogan Page

Tan, S. (2001) The Red Tree. Hachette; Australia

Tishman, S. (2018) Slow Looking: The art and practice of learning through observation. Routledge; New York

Related:

Banishing The Culture of Busyness

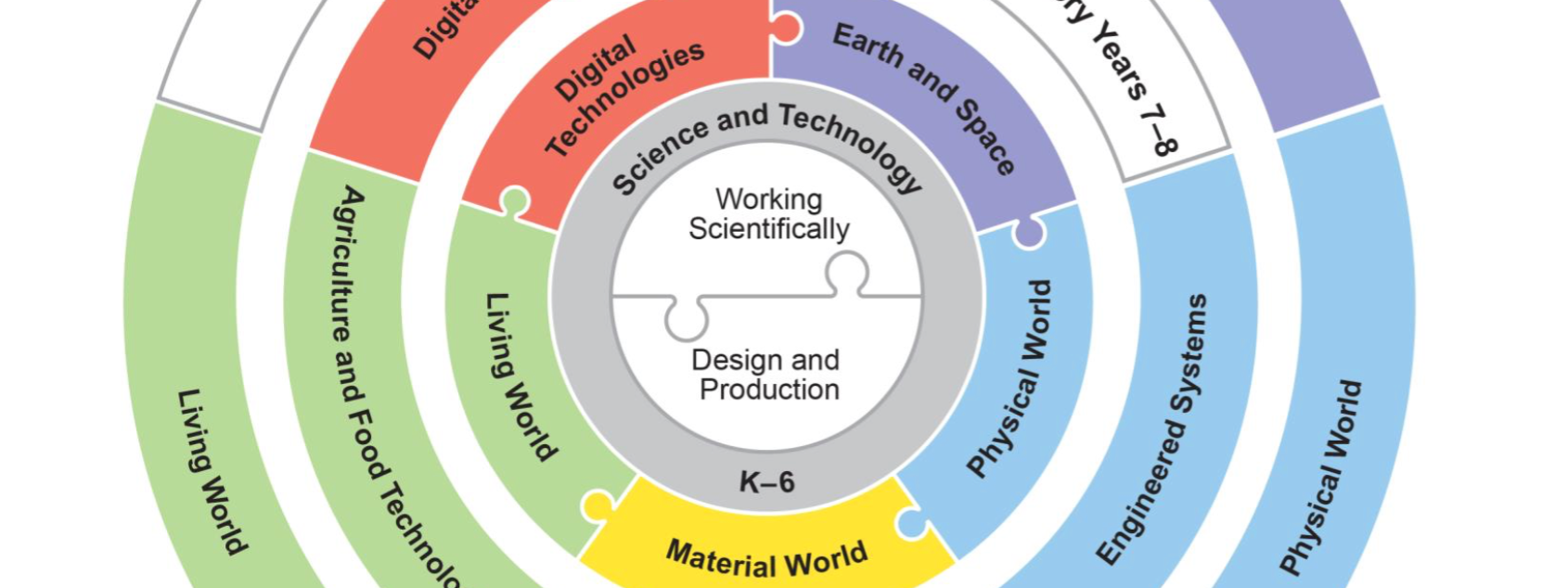

NESA (2017) Science & Technology K-6 Syllabus

Learning with the New Science & Technology Curriculum

In the final weeks of 2017 a new Science & Technology Curriculum for Kindergarten to Year Six slipped into the schools of New South Wales. What does this new curriculum bring and what does it reveal about the nature of learning as we approach the year 2020?

The Science and Technology Curriculum was updated quite recently. In 2012, it was released as part of the curriculum updates linked to the adoption by states of the Australian Curriculum developed by ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority). For some time now teachers have been expecting an update to incorporate the ACARA Digital Technologies syllabus. The expectation was that a new document would be released that would incorporate the skills, understandings and knowledge described in the ACARA syllabus alongside the existing Science & Technology syllabus.

The result is something different. What we have is a document with a focus on the application of approaches to thinking, problem finding and solving empowered by science and technology. It is perhaps a curriculum that will get students and teachers excited about science and technology. It also brings new challenges.

Read the curriculum and you discover a combination of the familiar alongside new ideas and a new emphasis. According to the syllabus:

Science and Technology K–6 is an integrated discipline that fosters in students a sense of wonder and curiosity about the world around them and how it works. Science and Technology K–6 encourages students to embrace new concepts, the unexpected and to learn through trialing, testing and refining ideas. (NESA, 2017 p12)

This is not a Science syllabus with an emphasis on content knowledge but one that encourages students to engage with the practices of the scientist, the curious explorer who embraces unexpected learning and has the skills to construct new knowledge.

These skills enable students to participate responsibly in developing innovative ideas and solutions in response to questions and situations relevant to personal, social and environmental issues. (NESA, 2017 p12)

It should be noted that unlike all other current syllabus documents, this one is aimed at students between Kindergarten and Year Six (5 to 12 year olds. The skills and dispositions described here are not those to be developed by students as they exit school but are the expectations for learners in their primary years; learning goals to be achieved before they enter high school. There is evidence here that contemporary thinking about curriculum design has found its way into NESA (NSW Educational Standards Authority):

Students studying science and technology are encouraged to question and seek solutions to problems through collaboration, investigation, critical thinking and creative problem-solving. (NESA, 2017 p12)

Use of the word “through” is worth noting. It is reminiscent of models for the curriculum developed by Alan Reid who suggested that a set of essential competencies should be the priority for the curriculum and that other content should be taught “through” the application and development of these competencies. In the science and technology syllabus you find:

Through the application of Working Scientifically, and Design and Production skills, students develop an interest in and an enthusiasm for understanding nature, phenomena and the built environment. (NESA, 2017 p14)

The knowledge and understanding in Science and Technology K–6 are developed through the skills of Working Scientifically, and Design and Production. (NESA, 2017 p24)

In this syllabus science is something that students do, a tool for exploration and inquiry rather than a knowledge base.

Through regular involvement in applying these skills in a variety of situations, students develop an understanding that the Working Scientifically processes are more than a series of predictable steps that confirm what we know. (NESA, 2017 p26)

This is very much so a syllabus that is entered on active and agentic students. Phrases abound such as 'Students question and make predictions', 'They pose relevant questions', 'Students explore', Students make observations', 'They use appropriate materials'.

There is also much here that supports the maker movement, indeed it is a required element of learning that students will engage with an active process of product evaluation, design, modification and production.

They question and review existing products, processes and systems, explore needs or opportunities for designing, define problems to be solved, (NESA, 2017 p27)

Students develop and apply a variety of skills and techniques to create products, services or environments to meet specific purposes. They select and use materials, components, tools, equipment and processes to safely produce designed solutions. (NESA, 2017 p27)

And across both Design & Production and Working Scientifically students are required to engage in practical activities, to learn by doing and by making with tools and materials. 'Students must undertake a range of practical experiences to develop knowledge, understanding and skills in Science and Technology’ (NESA, 2017 p25)

There is also a significant emphasis on thinking and the syllabus identifies four modes of thinking which are at the heart of STEAM learning. Computational Thinking, Design Thinking and Systems Thinking join Scientific Thinking to ensure that 'Productive, purposeful and intentional thinking underpins effective learning in Science and Technology.’ (NESA, 2017 p35) As the syllabus notes this will require scaffolds for students and strategies that they can deploy as they engage with opportunities to apply their thinking skills 'as they encounter problems, unfamiliar information and new ideas.’ (NESA, 2017 p35)

The scope of the syllabus is exciting and potentially engaging. If taught well and as intended it should go a long way to preparing students for future learning challenges. As an integrated approach to STEAM based learning with science, technology and approaches to problem solving at its heart it offers students opportunities to use their skills and knowledge in concerted efforts to solve problems that matter. How such an integrated approach to this type of learning is to be maintained as students enter Stage Four and the siloed world of disciplines that is typical in High School is not made clear. Will student find that science learning beyond primary school is not what they expected it to be even if what they have become used to is more closely aligned to the real world of science and technology?

The challenge is to provide Primary School teachers with the support in all its forms for this syllabus to be fully realised. Professional development, modelling of practice, mentoring and resources will be required. Genuine inquiry, design and production of the type outlined in this syllabus is both messy and comes with ‘unexpected’ costs. All of this will need to be planned for and the costs of this factored into budgets. Now that the document is available for implementation schools will need support in bringing it to life.

By Nigel Coutts

Culture, Change and the Individual

A recent post by George Couros (author of The innovators Mindset) posed an interesting question about the role that culture plays in shaping the trajectory of an organisation. The traditional wisdom is that culture trumps all but George points to the role that individuals play in shaping and changing culture itself.

"As I have connected with many educators around the world, they have often confided in me how different their school or organization has become because of that one person in that one new position. Sometimes it is a superintendent, principal, curriculum director, or a myriad of other administrative roles. Once in a while, that person makes it better, but more often than should be acceptable, one person in a short time can change the trajectory of a culture negatively."

(Read the full article)

George concludes that "one person can make the most significant difference on the whole”. So, what are the implications of this for those struggling to bring about cultural change? Is it the case that one person can indeed change the culture of an organisation? Is culture perhaps less resilient than we are led to imagine and is it just a consequence of the individuals with the greatest influence? Or, is something else at play here?

Fortunately for the field of sociology, culture is a complex concept. It is a co-construction of all those involved, the environment and the local and broader social context within which it exists and evolves. The culture of an organisation is difficult to understand and most efforts to describe the culture of an organisation will oversimplify the matter. Add to this what we have learned from post-modernist perspectives on the effects of observation and the complex dialogue between the observer and the observed and we see that culture is at least a messy field. Further along a continuum where at one end culture is a consequence of deliberate action and at the other it is as unpredictable as waves on a stormy sea we find complexity theory. Complex organisations, such as schools are described as emerging dynamically from their initial states but as these initial states are not fully understood the evolving organisation is seen to be on an unpredictable trajectory.

Complexity and Chaos Theories have much in common - Image - Pixabay

With this in mind it is not surprising that most efforts to bring about cultural change fail. A range of research studies cited by Burnes (2010) mention change failure rates of between 60% and 90%, with cultural change initiatives the most likely to fail. Mason (2008) does offer some hope for those wishing to bring about cultural change, ‘despite complexity theory’s relative inability to predict the direction or nature of change, by implementing at each constituent level changes whose outcome we can predict with reasonable confidence, we are at least influencing change in the appropriate direction’ (Mason, 2008 p46) Mason suggests that by making a concerted effort, at every point of contact available, change agents can drive cultural change at least in the desired direction even if not towards a desired goal. It might be possible to drive a school towards a focus on something like “quality teaching”, but the exact shape of that new culture is largely unpredictable.

This evidence points to the resilience of culture, it does not appear to be something that can be readily shaped, and yet as George indicates there are numerous examples of school cultures which have seemingly shifted with one change in staffing. How might this be so?

Change has, to a large degree become the norm in schools and the pace of change seems to be accelerating. From new curriculum, changes to assessments, measures of accountability, shifts in public perception, evolving and sometimes revolving ideals about pedagogy, to changes in the broader society that education serves, epitomised by the “new world of work” that our students will inherit, change is woven into the educator’s mindset.

With these changes, has come a shift away from teacher agency towards external control. Education is big business and a key factor in government policy. Driven by neo-liberalism and globalisation, education is shaped and controlled by factors which more often than not lie outside of the classroom. Standardised assessments, content heavy curriculums and teaching standards in an environment of competition and blaming of teachers for supposedly declining student performance have changed the shape of the profession.

The net effect of this climate of control and cyclical change is that teachers have adopted either a culture of compliance or silent dissent. Each change is viewed as fleeting, a new fad that will have its moment in the sun before slipping quietly into antiquity, replaced by something new. Teachers learn to bend with each new breeze or hide. What changes is not the culture of the school but the visible actions which sit on the surface. These superficial changes are easily implemented. They are actionable through efficient management or effective leadership. A change in leadership or key personnel is able to bring about change but the underlying culture remains as one of compliance or silent dissent.

The question then is what might it take to shift the culture of our schools from one of follow the fad to one where it is the norm for teachers to actively seek out what works best for their students. How might we create the conditions for a culture of creativity, collaboration and critical thinking within a profession that effectively communicates an understanding of what works for students to all stakeholders. How do we bring about genuine cultural change? Maybe it is as simple as restoring agency to those best able to do something good with it?

By Nigel Coutts

Burnes, Bernard (2010) 'Call for Papers: Why Does Change Fail and What Can We Do About It?', Journal of Change Management, 10 (2), pp. 241 — 242

Mason, M. (2008). What is Complexity Theory and what are its implications for educational change? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), pp. 35-49.

A Question of Scale: Meeting a Global Need

I recently spent ten days in Cambodia accompanying students on a service trip where they developed their cultural understanding and spent time improving the environment of a local school. While laying pavers and digging a ditch I had a chance to reflect on the difficulties facing education in a country like this. I came away with questions and few answers.

For the children of Cambodia education is critical to their future success. As the country races to move past the legacy of its recent history and build a stable economy and political structure its people recognise that education is going to be the key to success. Moves are afoot to get more children into school, off the streets and away from a life of begging and selling trinkets to tourists. Schools are replacing orphanages and organisations that focus on keeping families together are having success. By creating conditions that allow children to attend school while the parents earn a sufficient income to support the whole family, change is taking place.

Children are learning to read and to write in Khmer and in many cases in English. They are developing fundamental skills in numeracy and are learning about their country, the world and their place in it. When you visit a classroom, you see the very familiar scene of students sitting in rows of desks, the teacher at the front of the room delivering the lesson, asking questions, taking answers. The students have text books and readers. There are a few computers scattered around the school, there is a small library with a minimal collection of books. To meet demand the school runs on two shifts. One set of students attend in the morning, the second shift attends in the afternoon ensuring the school is able to serve the largest number of students.

Although the fundamental architecture of most schools might have changed little in the last century, digging beneath the surface shows that these classrooms have more in common with classrooms that were the norm in Australia and America in the early 80s.

What you don’t see are students engaged in project based learning, inquiry, independent research, problem solving or creativity. Learning here is about providing access to the essential skills and fundamental knowledge that the students need and only have access to when it is delivered by their teachers. Without ubiquitous access to free-flowing information from the internet, with limited access to information in books and literature the role that the school plays is not the same as it is in contemporary western nations.

The challenge is one of scale. How does a school system that is so stretched by demand that it must run two shifts each day, six days per week adopt modes of teaching that are more time consuming and require access to abundant resources? How do schools justify to parents programmes that are not tightly focused on developing essential skills in reading in numeracy or that do not match a model of schooling that is valued on the basis of its alignment with the perceived model of what school should look like? These are challenges facing progressive educators the world over but in Countries like Cambodia the pressure is enormous.

Clearly Cambodia needs an educated workforce if they are to compete in a global market, but what should the focus of that education be. It is difficult to argue against a focus on literacy and numeracy but what besides this should be taught. Perhaps more than anything else Cambodia needs a population adept at creative problem solving. A youth empowered to look at the problems facing their communities and see in these new opportunities. Will reading, writing and counting be sufficient for this?

Change is undoubtedly coming. Thanks to mobile internet access to information is exploding across the country. Here scale and growth are working in favour of the people. The cost of data is being driven down by demand and with this comes new possibilities for education. Currently a significant inhibitor of access to education beyond school or beyond the narrow curriculum schools can deliver is the cost of text books. Access to low cost data will overcome this barrier and bring with it opportunities for a greatly expanded curriculum. With cheap data comes access to a world of learning fueled by online courses and MOOCs developed for the western nations and available globally. Self Organised Learning Environments (SOLES) become a possibility and bring further opportunities for learning.

What changes will need to occur within Cambodian schools so that they might maximise the benefits that mobile internet will bring? How will teachers be provided with the skills they need to transition from being dispensers of knowledge to facilitators of learning in an internet enhanced classroom? How will schools continue to be havens of learning and places of safety where children can focus on having their needs met when learning moves into the cloud and can occur anywhere, anytime?

Cambodia is one example of a nation confronting these challenges. Its recent history brings the unique challenge of a population that is disproportionately young (Average age is 25.3 years compared to Australia at 38.7 years). These challenges are occurring across the entire developing world, millions if not billions of people demanding a brighter future where the fruits of education translate into a world of work that rewards smarts, not physical effort alone. How will education meet this challenge and does a contemporary education focused on creativity, collaboration, critical thinking and communication scale to the extent required?

by Nigel Coutts

Related - Reflections on a Service Trip to Fiji

Exploring the Changing Social Contexts of Learning

Contemporary learning environments might be best understood when viewed as a complex mix of environments and overlapping social networks. Learners fluidly move between social networks and their learning is influenced by their participation within and across these physical and virtual networks. Understanding how mobile, global and virtual social networks influence our interpretation of socio-cultural theories of learning might allow us to better understand the interplay of settings and contexts within which learning occurs and in doing so better understand how learning may be facilitated.

The socio-cultural perspective on education has its origins in the work of Lev Vygotsky (Göncü & Gauvain, 2012) and is an approach which considers the individual and their interactions with the social environment as central to understanding the processes of learning. Learning is said to be that which occurs through interaction between the individual, and all that their biology brings to the table and the social context in which learning occurs. Such an approach shifts our thinking about learning and development as processes contained and constrained within the individual’s biology to a more diverse understanding that incorporates the social context within which all learning is seen to occur. For educators, this approach encourages us to look at the learning environment and the social context in which the learning we design for our students occurs and 'presents a fuller and more accurate picture of children’s learning and development.' (Göncü & Gauvain, 2012 p126) Sociocultural, and the in some ways related social-cognitive approaches build upon earlier research that focused on the individual as the unit of development but seek to explain the differences which were observed across groups and contexts which could not be explained without a wider frame of reference.

By expanding the frame of reference to include the social context within which learning and development occurs a more complex image emerges of the interactions and processes which are at play. Vygotsky's (1978) research shows how interactions between the child and their social environment enables learning. He explores the gap between what a child can do now independently and that they can do with assistance. Termed the 'Zone of Proximal Development’(ZPD), this is the gap into which teachers hope to move their students (Vygotsky, 1978). Teaching strategies such as formative assessment (Black & Wiliam, 1998) seek to identify where the ZPD is for students and then provide appropriate learning situations which scaffold student’s growth through this zone. Effective teaching will provide a context that allows students to achieve success on learning initially pitched within this zone with guidance while moving towards internalisation of new learning evidenced by success when the scaffolds are removed. It is with this process in mind that we develop teaching programmes and curriculums.

Given the multitude frames which might be used to inform our understanding of what culture is, (Jary & Jary, 1991) how it is constructed and how it shapes and is shaped by interactions with individuals and groups it unsurprising that there are multiple perspectives upon the nature of socio-cultural learning. This complexity is expanded when comparisons are made between socio-cultural perspectives and social-cognitive perspectives are considered. Emerging from the work of Albert Bandura (1977) social-cognitive theories like socio-cultural approaches are concerned with the learning that occurs within societies and the cross-cultural differences which such perspectives reveal. 'In contrast, social cognitive researchers have devoted considerable attention to the role of social variables in learning, how motivational processes affect learning, and how social cognitive principles can be best applied to enhance students’ learning from instruction.’ (Schunk, 2012 p117) A further differentiator is evident in the significance given to vicarious learning or learning purely through observation of others that is present in social-cognitive theory but is not evident in socio-cultural theories which emphasise translation of observations of others into action or learning by imitation of the observed behaviours. Social-cognitivists would show that learning can be acquired without the imitation phase.

For teachers, social-cognitivist approaches shine a light on the factors which result in motivation towards learning. Learning is said to be enhanced when individuals have positive self-efficacy for learning (Bandura 1977). Motivational theories such as self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and attribution theory (Weiner, 2004) point to factors such as autonomy, purpose and mastery (Ryan & Deci) and locus of control (Weiner - internal/external stable/unstable controllable/uncontrollable) as key factors which influence engagement and perceptions of success. In social-cognitive theory these factors are described as acting upon the individual through changes in levels of self-efficacy. When social aspects of learning are accounted for the provision of a safe, supportive and nurturing learning environment is broadly considered to be significant (Tirri, 2011)(Marzano & Pickering, 1997). The complexity of social environments within which learning occurs presents challenges to educators looking to manage the environment in which learning occurs. Students are less likely to engage with challenging learning in settings where they feel unsafe or believe that their attempts to engage are likely to be judged negatively or where the rewards available are low. (Atkinson, 1957) (Dweck & Legget, 1988) (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000).

A shifting emphasis on what is valued as the outcome of formal education places greater emphasis on the capacity of individuals to be creative collaborators. In ‘Participatory Creativity’, Edward Clapp (2017) details the importance of collaborations between individuals in a form of collective agency derived from the work of Bandura. Collective agency acknowledge the role of the individual within efforts of a greater collective. Informed by this perspective and Cskiszentmihalyi’s view of creativity as a product of social systems, Clapp builds a model of creativity that results from the collective efforts of society and focuses on the processes through which ideas evolve rather than a more traditional view which attribution of a product to an individual. Creativity in such a model is like learning in socio-cultural perspectives a social phenomenon.

Significant differences in the socio-cultural setting within which the individual experiences learning can be shown to account for varied outcomes. An example of this can be seen in the exposure to language which occurs in different settings. Hart & Risely (2003) show that a five-year-old child growing up in a home with parents categorised as professionals would have been exposed to 45 million words. By contrast a child growing up in a working-class family would have been exposed to 26 million words and only 13 million if growing up in a lower-class family. This gap in exposure must be seen as more significant than a deficit in vocabulary within a socio-cultural perspective that emphasises the development of language as a critical component for development in general. According to Vygotsky, children learn to use language regulate their psychological functions (Göncü & Gauvain, 2012) and language is an essential tool in the scaffolding and modelling of learning that occurs both within schools and other environments in which learners learn. This gap in exposure presents significant equity challenges for educational systems.

Traditionally the socio-cultural setting in which learning and development occurs has been defined by the physical settings in which the learner is situated and the culture that is attached to that. Relationships between the individual and their immediate family play an important role in the early years of learning, as the child grows the social context in which they learn widens and peers, teachers and the wider community begin to play a part. As the child interacts with a growing number of social contexts they are able to draw upon an expanding set of models and observations as they learn to regulate their behaviour and adopt (and modify) the cultural norms required for adult life (Göncü & Gauvain, 2012). In more recent times this social context has become increasingly difficult to define.

Through a variety of factors, such as globalisation, increased mobility and technology enabled networks, the individual is increasingly found to exist simultaneously across multiple cultures and societies (Leander, Phillips & Taylor, 2010). These multiple contexts and cultures bring to the learner new challenges and require learning of multiple norms along with the pressure to activate the appropriate norms for each context.

The once clear boundaries of the social context of learning and development is increasingly blurred and stretched by technologies and networks. In seeking to understand how this space influences learning and development it is necessary to consider the individual, the interacting social networks (physical and virtual) and the technology as agents which influence development. At best the experienced reality is ‘complicated’ (Boyd, 2014) as the individual within the virtual world is able to fluidly shape and reshape both identity and context. 'When teens engage with networked media, they’re trying to take control of their lives and their relationship to society. In doing so, they begin to understand how people relate to one another and how information flows between people.' (Boyd, 2014 p92) The blurring of social contexts further complicates the learning environment experienced by young people when it is recognised that they spend much of their time living within a culture that the adults in their world know little about. The norms, language, symbols, signs and meanings of the virtual worlds may be borrowed or appropriated from the physical world but are often wildly misinterpreted when decontextualised. Further still access to resources, knowledge and tools derived from technologies and their networked lives are viewed with suspicion in many traditional learning environments thus bringing artificial barriers to learning and de-contextualising the skills learned in school from those valued in the ‘real world’.

From the research of Vygotsky, Bandura and others across socio-cultural and socio-cognitive perspectives we have been provided with a theoretical tool kit with which to better understand the interplay of the individual, society and culture. As we move further into an age dominated by technology and networks it is incumbent on all those with an interest in learning and development to look at the interplay of forces which act upon the individual. By seeking to understand the influences that physical and virtual contexts have on learning we can begin to imagine a model of education which makes best use of the diverse environments in which our young people are immersed.

By Nigel Coutts

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64, 359–372.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998), Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment, King’s College, London: School of Education.

Boyd, D. (2014) It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Csiksgentmihalyi, M. (2013) Flow: The psychology of happiness’ and creativity: The psychology of discovery and invention. New York; Harper Perennial.

Clapp, E. (2017) Participatory creativity: Introducing access and equity to the creative classroom. New York: Routledge

Dweck, C., & Leggett, E. (1988). A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273.

Göncü, A., & Gauvain, M. (2012). Sociocultural approaches to educational psychology: theory, research, andapplication. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, and T. Urdan (Editors-in-Chief). APA Educational Psychology Handbook: Vol.1. Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues, 125-154.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. (2003). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator 27(1), 4– 9.

Jary, D., & Jary, J. (1991) Collins dictionary of sociology; second edition. Glasgow: Harper Collins.

Marzano, R. & Pickering, D. (2009) Dimensions of Learning: Trainers manual 2nd Edition. USA: ASCD Publications.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Schunk, D. (2012). Social cognitive theory. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, and T. Urdan (Editors-in-Chief). APA Educational Psychology Handbook: Vol.1. Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues, 101 -123.

Tirri, K. (2011) Holistic school pedagogy and values: Finnish teachers’ and students’ perspectives. International Journal of Educational Research 50 pp159-195

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. (M. Cole, Trans. & Ed., V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1934)

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81

Inquiry vs Direct Instruction - The Great Debate and How it Went Wrong

There is a debate taking place in the world of education. It is not a new debate but recently it has gathered new energy and the boundary between polite discussion of opposing views and hostility has been stretched. The debate is that between those who are advocates of inquiry based learning and those who believe direct instruction produces the best outcomes.

Like most conversations which occur within the public sphere of the online social media world, the debate has quickly devolved into a dichotomous debate where each side seeks to win points at the expense of the other. Humans have a natural tendency towards tribes, as biologist Edward Wilson writes "The tendency to form groups, and then to favor in-group members, has the earmarks of instinct.” It is a characteristic that may have once served us well but in modern times it focuses our attention on what makes us different rather than helping us to find a common ground. In debating topics like direct instruction vs inquiry based learning our tendency to form tribes causes us to drift from a rational position to a more extreme and one sided view.

There is in this debate a middle ground. Claxton and Lucas deal with this debate and the reality that most educators fall somewhere between the two extremes in their book Educating Ruby. They place Trads (traditionalists focused on knowledge transfer) and Roms (romantics who feel children learn by osmosis) at the extremes of the educational spectrum and Mods (Moderates) in the middle. "Almost everyone who works in education is a Mod. But because Mods prefer to tinker quietly than to bang big drums, it is easy to underestimate how many there are” (Claxton & Lucas, 2015)

The middle ground between Inquiry and Direct Instruction is that place where we take a little from option A and a little from option B. Sometimes we go with direct instruction and at others we go with an inquiry approach. This leads to models where children are taught the supposed fundamentals of a discipline or topic and then allowed to engage in some inquiry. Sometimes this model works, sometimes it misses the point. Often the inquiry component is redundant by the time students get to it, sometimes the direct instruction is an opportunity to lecture at students, sometimes the students are told what they need to know but are not taught how to make effective use of it.