Teaching and subsequently learning can be seen as a consequence of key messaging systems such as curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. For organisations charged with the provision of education, management of these systems is essential. While other factors such as culture play a role in setting the final shape of the learning that occurs in our schools, the big three of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment are most open to manipulation. Quality teacher frameworks and teacher evaluation methods influence pedagogy and governments have increasingly taken charge of curriculum with many countries moving towards national or common core curriculums. The role of assessment has always played its part but it is a role that is changing in the present global climate and understanding this shift is important for educators.

National assessment programmes are one mode of control used by governments and are commonly cited in the media to support initiatives that shape education. In Australia, NAPLAN (National Assessment Programme, Literacy and Numeracy) plays a significant role in establishing particular aspects of Literacy and Numeracy as a priority for educational programmes. Although broadly criticised as narrow in focus and lacking the finesse required of a diagnostic tool, NAPLAN results are used to inform curriculum design, focus teacher efforts and evaluate schools. As a strategy towards constructing a market place for education and for encouraging parental choice in schools NAPLAN has become a powerful force in Australia. NAPLANs design can be seen as a response to a ‘back to basics’ and fundamentals approach to teaching, which has been cyclically popular in Australia, as much as policy shifts may be described as a response to the data it produces. NAPLAN if nothing else reveals something of the political imperatives which shape education as it reveals what those who shape policy consider important to measure.

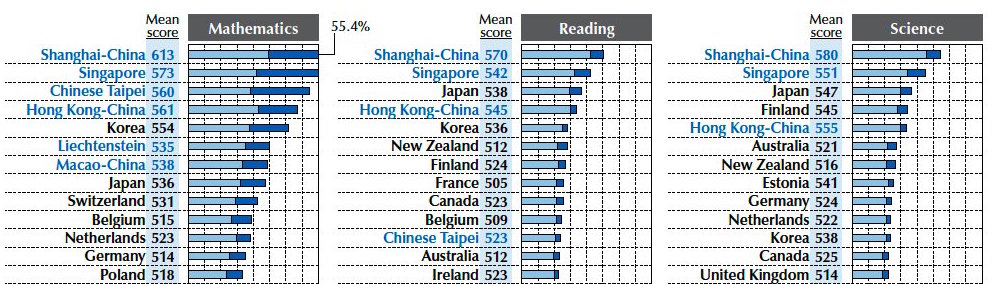

Increasingly education is a global market. As Ken Robinson points out, there is a trend towards comparisons of national education systems that was neither desirable nor possible but a short time ago. This trend towards international educational comparisons reveals winners and losers on a global scale. Finland was the darling of this global market, now Asian markets such as Shanghai-China, Singapore and Korea are topping the lists according to the data produced by PISA, the Program for International Student Assessment. A quick search on Google will return a sorted list of countries with scores indicating their comparative performance on this test and not on education sites but on Business Insider Australia. Education is important to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) and its global assessment programme is one way that it demonstrates this and plays a part in shaping educational reform.

A host of testing programmes are increasingly shaping education and the use of their results in reporting on education and in pseudo-educational research as reported in the media is difficult to ignore. PISA may have the dominant place but TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) and PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) have parts to play. What is rarely reported is how these assessments are implemented, what they actually assess, who and how many are assessed and what measures are used to ensure validity across years of implementation. While TIMSS and PIRLS are by name focused on specific aspects of learning PISA is a more open assessment and while its results are reported in terms of performance on Mathematics, Reading and Science its scope is wider and varied across implementations. In each case it should be noted that only samples of students are tested and that as is the case with all assessments delivered on such a large scale the results are not intended for identification of individual learning or even learning within a particular school. National results rising or falling do not indicate a similar trend within any one school and a single score can only reveal the broadest strokes of what may be occurring within a country. After slipping on the PISA ranking Pasi Sahlberg, the popular face of education in Finland indicated that 'the discussion is about how Finland can improve the system as a whole and increase enjoyment in learning. It is not just about how to improve our performance on PISA.’ An approach not copied by other systems less confident in their methods.

The shaping of PISA by the OECD reveals the priorities it has for education within a view of international economic development driven by market forces and and neo-liberalism. Interviewed by EdSurge recently Andreas Schleicher, the director for the Directorate of Education and Skills at the OECD revealed how PISA responds to market pressures. 'We look very carefully at the evolution of skills demanded in our society. Many of the skills that schools have traditionally emphasized—memorizing things and then recalling them—are becoming less and less important for the success of people. In contrast, creative thinking, collaborative problem solving and social skills are becoming more important. We look very carefully at how the world and the skills that people need are changing and then we try to reflect that in our measure.’ This style of evolution within PISA in response to external demands for graduate skills shifts the focus of thinking within education systems. In this way the OECD is able to direct policy at a national level and in response to a very particular world view on the role that education plays in meeting the demands of economic development.

Sahlberg states that 'Schools need to help many more people find out what their strengths are, what they are curious and passionate about. The school system should be designed to inspire students and to enable them to lead happy, fulfilled lives both at work and outside of the workplace.’ Much of this falls into categories which are difficult to assess and build systems to achieve. PISA is looking to include measures of resilience and motivation in their tests which is a positive sign but will this be reflected in the reporting of the results given the existing trend to condense the breadth of data available to score on limited measures.

There is a divide here between what our students need from school and what schools and nations need from their students in terms of positive test results. As long as the emphasis is on a limited set of scores and while the international testing scene is driven by market forces for economic development a full and broad education for all seems like an increasingly distant goal.

by Nigel Coutts