Society confronts educational change in an odd, entirely counter intuitive manner. On one hand we acknowledge that education can and should do a better job of preparing our children for the future while on the other we cling to the models of education that we knew. This led educational writer Will Richardson to state that ‘the biggest barrier to rethinking schooling in response to the changing worldscape is our own experience in schools’. Our understandings of what school should be like and our imaginings of what school could be like are so clouded by this experience that even the best evidence for change is overlooked or mistrusted.

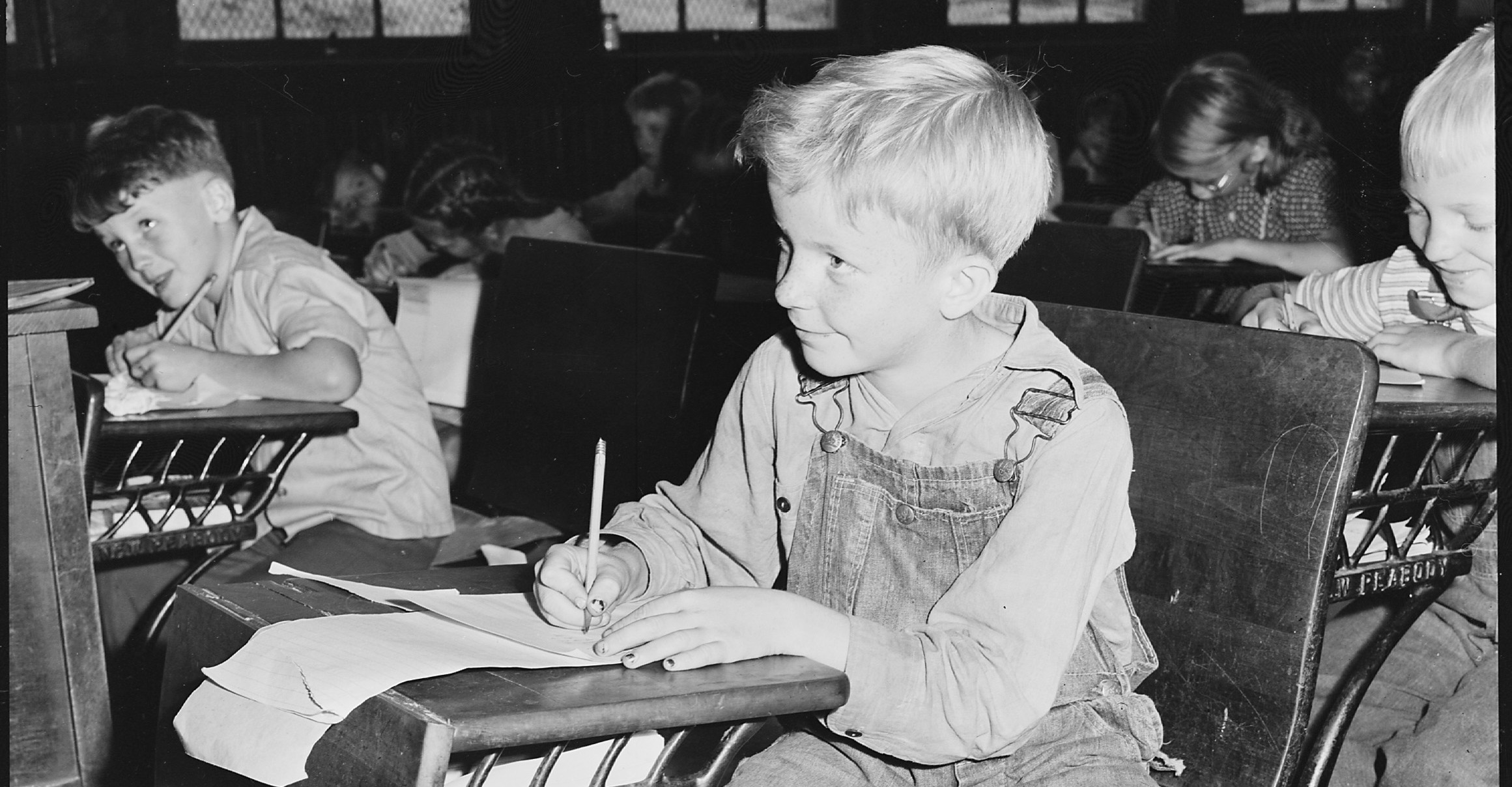

When I reflect on my years in school I find little that was so compellingly inspiring that I would wish for similar experiences to be shared with the children I teach today. Male teachers were known as ‘Sir’, female teachers as ‘Miss’. This naming ritual made for difficult conversations when the instructions of a specific teacher needed to be communicated. ‘Sir sent me with this note’, ‘Who?’, ‘Sir’, ‘Which Sir?’ ‘I don’t know’. I recall the smell of freshly printed worksheets, the purple ink smudging under my plams. I remember the day my Year Six teacher had to go home in the morning due to a malfunction of the Gestetner machine. Many lessons involved copying notes from the board into our books, a style of learning (torture) that although rare today lives on in advice from psychologists that students with vision or attention difficulties should be seated near the board to make this task easier.

I recall very little of what I was taught. Years of Latin left me with a vague understanding of some Italian and the phrase ‘Canis est pestis et furcifer’. To ensure this phrase has ongoing utility in my life I have two dogs, although they are rarely either pests of scoundrels. I remember a teacher who encouraged me to ask questions in science lessons and who was willing to admit he did not know the answer but would be keen to help me find it. An English teacher with a passion for fantasy introduced me to a world of amazing literature by sharing his personal reading habits with the class. I was fascinated by certain elements of History but it has left me with knowledge that I seldom need. My handwriting was atrocious and despite many extra recess lessons spent meticulously copying letter forms from a text book is only slightly better today. If it were not for typing I would write very little as an adult.

Image courtesy Wikipedia

My school days left me with a belief that there were ‘smart’ students and the rest of us. I was one of the students who made the top ‘fifty-percent’ possible. It was many years after school before I learned that being smart is a result of the choices you make, of the effort you apply to mastering something and your self-confidence; that intelligence takes many forms and is not fixed. Only recently I have been shown that even Alfred Binet, inventor of intelligence testing, did not see intelligence as unitary or fixed but as a complicated mixture of skills and abilities. Carol Dweck’s work on growth mindsets was surely needed in the lives of many students exposed to educational systems that had more to do with ranking students on a curve than developing their capacity for success.

In the best classrooms today things are different. Students are engaged in learning that challenges their thinking, connects with their interests and lives, has meaning beyond the classroom and requires the development of their socio-emotional intelligence. They are not required to engage in pointless and repetitive tasks such as copying notes from a blackboard. Worksheets are a thing of the past. The notion of ‘work’ is one that should be eradicated from schools, replaced with a clear focus on ‘learning’ as our raison d'être. Teachers are people to connect with and learn with as collaborators and co-constructors of knowledge. Learning is 'life-worthy' as David Perkins describes it, that is ‘likely to matter in the lives that learners are likely to live'. Long-life skills are the focus of learning and students are encouraged to seek answers to the questions that matter to them and that they discover.

The quality and consequence of this change is easy to see and it is reflected in conversations I have with visitors to my classroom. It is not uncommon to have adults exclaim that they wish they could be participating with the sort of projects they see their children engaged in. ‘We didn’t get to do that when I was at school’ is a common observation made by visitors plainly excited by the learning they see. But the observations identify more than highly engaged students. Many of the visitors note that they would not have been able to complete the sort of complex learning experiences that children today take for granted. The rote learning methods of the past did little to prepare us for problem solving and offered few opportunities for thinking; both of which are increasingly the norm.

I am certain that my parents when visiting me in school never longed to be back in class with me completing worksheets. Education in modern times should be highly engaging, challenging, thought provoking and stimulating. The student’s learning has relevance beyond the classroom and points to the reality of learning as an essential part of life and not merely an activity confined to twelve or so years of formal schooling. We need to let go of our visions of what school was like and begin anew with a dream for what school might be like. There are many experiences of happiness, joy and even sadness that we should share with our children but an educational legacy of disengagement and irrelevance should not be among them.

By Nigel Coutts

Bill Lucas and Guy Claxton (2010) New Kinds of Smart: How the Science of Learnable Intelligence is Changing Education. Open University Press

Carol Dweck (2012) Mindset: How you can fulfil your potential. Robinson

David Perkins. (2014) Future Wise: Educating our children for a changing world. Joey Bass; San Francisco

Will Richardson. (2015) Freedom to Learn. Solution Tree