An important part of the role of any educator is that of planning learning sequences. Perhaps you are tasked with designing curriculum or more likely you are translating a mandatory curriculum into workable units of learning. The task is complex and there are multiple arrangements.

The goal is to design units that connect students with learning in ways that are meaningful and relevant. A well-designed unit of learning fits seamlessly alongside other learning opportunities and the overall sequence of learning should match the learner’s developing expertise. As we plan units of learning we must consider a great variety of factors which impact the learning we design. Our knowledge of our students and where they are with their learning is crucial and a strong place to start. We also need to know what it is we are required to teach and have a grab bag of pedagogical moves that bring this content alive.

Deep pedagogical content knowledge allows us to see the big picture of what we need to teach and how we can best arrange it into a compelling learning journey. Thanks to an overcrowded curriculum and our awareness of the need to teach beyond knowledge the task of deciding what content, skills and dispositions will make the best combination for our learners is challenging. As we move towards interdisciplinary and trans-disciplinary the possible combinations expand and the planing becomes increasingly complicated.

Traditional planning methods can be quite restrictive. The norm is to plan a sequence of lessons from the introduction to the unit through to its conclusion. This linear planning method is largely dictated by the media used to document our units of learning. A traditional teaching and learning programme will be planned out using some version of a word processing application. There is likely to be a rationale and series of outcomes clarified on the first page. Perhaps there are some understanding goals and essential questions. There is likely to be a list of resources. The inside pages describe what the students and teacher will do. There are links made to the outcomes, possibly learning objectives for each lesson and there are check-ins and assessments described to evaluate student progress. At the conclusion, there is likely to be some form of summative assessment, a reflection on the learning and space for the teacher’s evaluation of the unit.

Look at a range of programmes developed in this manner and you see in part how the grammar of school is shaped by the modality of our planning. Just as our planning follows a linear progression from one activity to the next so too does the teaching and learning that results from this. The pattern is set not by the learner, our beliefs about learning and our awareness of effective pedagogy but by the nature of how we plan. We may well understand from experience that learning is messy and that the path taken in achieving an understanding of new concepts is unlikely to be the same for all students but our planning does not make designing for this complexity easy.

This linear planning can also rob us of a big-picture vision of the learning opportunities that exist. As we follow the programme we see each piece of learning in isolation. The fit between outcomes, skills and dispositions can be difficult to see and if we as teachers can’t see it how will we make this evident for our learners? The failure to see the big picture also denies us opportunities to see potential connections across the content we are to teach. A more expansive view of our curriculum should allow us to identify and then explore connections between content, skills and dispositions. This expanded view allows us to move from ideas in isolation towards concepts and big understandings. When we begin to see the curriculum in a more holistic manner we also see where ideas are duplicated and time can be saved by not dealing with similar ideas in isolation multiple times.

What we need is a planning tool that allows us to see the connections between the content, skills and dispositions we need to teach and that our students need to learn. A non-linear model that better suits the complexity and messiness of planning for learning benefits from a tool that encourages big-picture thinking. Fortunately, there are a number of such tools available.

Some teachers might remember Inspiration and Kidspiration as software that made mind mapping popular in the early days of computing. They were once the darlings of ICT integration and they were used almost ubiquitously in schools. Today modern alternatives are available with cloud integration and versions with many of the features you most require free of charge. My current favourite is LucidChart.

LucidChart and similar applications make it easy to organise ideas in whatever manner suits you. Drag shapes into the document, move them about, change their size, colour, border. Text can be added to any shape and -reformatted shape and text combinations can make the process easier. Easily drag links from one shape to another as you explore connections between content, skills and dispositions. Use a variety of shapes and colours to show related ideas. Use tessellating shapes (I like hexagons for this) and you can nest shapes together. Links can be made to other LucidChart documents or to any page with a web address. When you are ready to share your thinking there are multiple options including a presentation mode, options to download in common formats such as PDF, JPEG and PNG or you can share to a cloud service such as Google Drive.

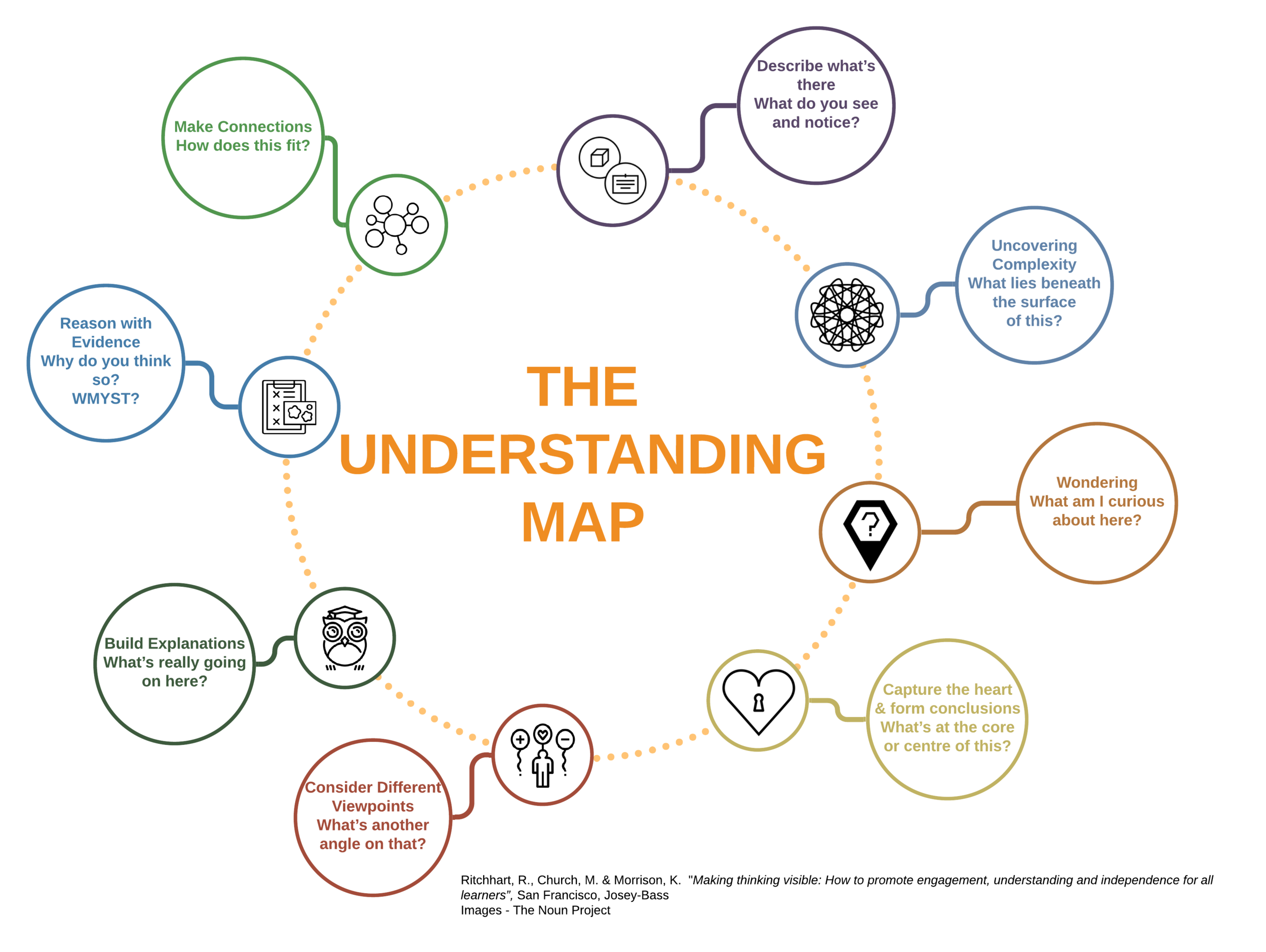

The examples below were created using LucidChart. The first shows the thinking moves as identified in Ron Ritchhart’s “Understanding Map. The second connects ideas from the “Understanding Map” and the TEEL paragraph structure. Icons are courtesy of “The Noun Project”.

LucidChart is available as a web-based application in any modern browser or as an application for iPad and Android. There are free accounts available for Education users with verification of an EDU email.

By Nigel Coutts