What’s worth understanding? What best builds understanding?

These two powerful questions framed a recent webinar presented by Professor David Perkins of Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero. Answering these questions and helping teachers find meaningful and contextually relevant answers to these questions has been a focus of Perkins’ work, especially in recent times. His book “Future Wise: Educating Our Children for a Changing World” introduced us to the notion of lifeworthy learning or that which is “likely to matter in the lives our learners are likely to live”. This is a powerful notion and one that has the potential to change not only what we teach but also how we go about teaching what we do.

In uncertain times, there is a greater need to reflect upon these questions. “What’s worth understanding?” in a world where uncertainty is the norm. What learning might be of the greatest utility to our students as they confront a rapidly changing and ambiguous future? How might we know today, what learning will be lifeworthy in the lives our learners are likely to live when uncertainty is the norm? It was with this in mind that Perkins engaged his audience. This is a topic I have touched upon previously:

These are times of chaos, complexity and contradiction (Sardar, 2010) where education is challenged to reimagine how it prepares young people of today for their worlds of tomorrow. Confronted by rapid change from a conflation of transformative forces society appears to be in a state of flux. The grand unifying socio-political stories and underlying structures that we have relied upon in the past seem to have dissolved under our feet leaving us bewildered (Harari, 2018). The beliefs, values and philosophies which we once relied upon for guidance, trust in reason and science, the valuing of human intellect and our understanding of fundamental political systems have been replaced by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (USAWC, 2019). The exponential acceleration of the capabilities of our digital systems carries with it a transformative potential with far-reaching consequences and opportunities (Friedman, 2016). Similarly, our reliance on technological innovations that emerged during the first industrial revolution is today driving climate change and represents what David Attenborough describes as our greatest threat (Attenborough, 2019) “All that was ‘normal’ has now evaporated; we have entered postnormal times, the in-between period where old orthodoxies are dying, new ones have not yet emerged, and nothing really makes sense.” (Sardar, 2010 p. 435)

The challenge then is to identify that which is “lifeworty”, and to this, Perkins invites his audience to engage thoughtfully with the process of evaluating what’s worth understanding. This mode of operation is typical Project Zero. The easy approach would be to offer teachers a curriculum of what might be considered lifeworthy. Such an approach, however, robs the teacher of agency, inhibits genuine engagement with both process and product and overlooks the diversity of contexts in which the question “what is worth understanding” is likely to be asked. Further, an organisation that values thinking so highly is behoved to bring opportunities for thinking to all that they do. By engaging his audience in a process of contemplating what is lifeworthy he models the thinking and learning processes that are at the heart of Project Zero’s philosophy of conducting high-quality research that enables a fresh perspective on what might be achieved in the classroom. Not a Seven Steps for success methodology but revelations that inspire conversation and empower teachers to do what they do better.

What learning mattered to you? What did you learn at school that you continue to rely on routinely? What did you learn at school that you have not used since leaving?

Perkins here asks his audience to consider the opportunity stories attached to the themes or topics that they are currently teaching. He uses the French Revolution as an example of a topic which can be taught in limited and restrictive ways, or that can be transformed by a teacher who looks for the opportunity story of the topic. A teacher could easily teach students all of the facts relevant to the French Revolution. Students would exit the unit with a vast repository of knowledge. They could answer questions such as when did it begin? When did it end? What were its causes? Who were the key people? What part did each play? But teaching the French Revolution in this way is unlikely to be of significant value in the lives that learners are likely to live beyond maybe giving them an edge at a French-themed trivia night.

But, the French Revolution should not be abandoned as a topic. Instead, the teacher needs to seek the opportunity story that it offers. When we go beyond knowing, beyond facts and beyond the specific, we see that the French Revolution can have a vibrant and expansive opportunity story. What might the French Revolution tell us about other revolutions? What might it reveal about change or of warfare and the human drive to conquer? How might the French Revolution be used as a metaphor for the study of modern revolutions such as the digital revolution of the 21st century? What might it reveal to us about conflict resolution, or politics, or business management? When we go beyond the minutia of the topic, we begin to unravel an opportunity story that reveals a topic’s great potential as a tool within a lifeworthy curriculum.

Through the French Revolution, I was able to understand the generalities of world conflict...for instance, how the lack of freedom, poverty, over-taxation, weak economies, the struggle between the Church and state, or social inequity has always been a reason to engage in war.- Perkins 2020

Understanding Of VS Understanding With

The content-heavy, knowledge-focused approach to the French Revolution described above is indicative of a drive for ‘Understanding Of’ a topic. We might finish the unit with a detailed understanding of the topic, but we have learned little else. The more expansive model where the French Revolution is used as a catalyst for an investigation of significant historical, political and sociological themes is an example of a drive towards ‘Understanding With’. We finish the topic with an understanding of the essential information about the French Revolution, and we also exit with a broader perspective on the world and a new way of understanding many interrelated topics. We have developed understandings with our study of the French Revolution rather than merely developing an understanding of the French Revolution.

The French Revolution is a beautiful example of a topic ready for transformation via an analysis of its opportunity story. Not all topics, however, offer so many possibilities. Some are perhaps just not going to meet our needs if the goal is a life worthiness. Perkins uses the quadratic equation as such an example. He invites the audience to consider a series of questions:

How many people have used the quadratic equation vs How many people have learned the quadratic equation?

How many people have used the quadratic equation outside of an educational setting?

Very few people use the quadratic equation outside of a mathematics lesson

What lives on from this learning in the lives of most learners?

When judged against this set of questions, we are left wondering if the time spent on teaching students the quadratic equation might be better used elsewhere. Perkins makes it clear that this is not an attack on mathematics. The same set of questions, when applied to statistics and probability, reveal a very different response and show a topic with a broad and meaningful opportunity story. Indeed knowledge of statistics is almost essential in navigating the modern world where numbers are routinely manipulated to manipulate us.

What’s most worth understanding? - The importance of Wonder

Perkins reminded his audience that learning should be about more than practicality, more than just business, the needs of the economic engines of industry or of our duties as citizens. - Learning should also be about questions and wonderings that stir our heart. Learning that matters includes room for what inspires us, what intrigues us and makes us wonder how can that be? More than just a foundation for the practicalities of life but a grounding for the capacity to transform wondering into action. In this sense, we are learning how to wonder and what to do with our wonderings. We are developing a disposition towards wonderment where we have the capacity to wonder about our world, a sensitivity for the possibility for wondering and the motivation to not only wonder but to act towards the satisfaction of our curiosity. It might well be noted that a disposition for wonderment is perhaps one that we need to have reinstated if it is something we left behind in childhood.

To help us bring more lifeworthy learning into our curriculum, Perkins offers the thinking routine Mattermatics. It is a routine that invites us to consider what we want to add to our curriculum that is not already there, what we would like to do more of and what we would like to do less of. The name deliberately sounds like mathematics to reference the use of the mnemonic:

+ 1 What’s one theme or topic you would add to move you towards lifeworthy learning?

x 2 What’s one theme or topic you might expand to move towards lifeworthy learning?

÷ 3 What’s one theme or topic you might shrink to make room for more lifeworthy learning?

What best builds understanding? - Understanding in Action

How do we understand Understanding or what do we mean by understanding is a topic central to the opera of Project Zero and the core idea behind Teaching For Understanding. Many young students have a limited and limiting perspective of understanding. They hold in their minds an image of understanding as having possession of knowledge. This extends to common perceptions of what it means to be smart or wise or educated. Project Zero encourages a broader perspective - an action perspective or a performative perspective. By this definition, understanding requires a set of skills and knowledges that you can do meaningful things with - the ability to do meaningful things with what you know.

With this conception of understanding in mind, how do we begin to transform the nature of the learning that our students engage with to better focus on developing lifeworthy understandings? Perkins suggests that we look for the’ toolkit’ of useful things that our topics offer. If we look back at the topics exemplified above, we may consider the quadratic equation to be equivalent to a bread knife. It serves one purpose, and even if we try to adapt it to others, its utility remains limited. The French Revolution, by contrast, might be seen as a Swiss Army knife. It brings many options and has a broad set of affordances. Having identified a topic that has such breadth, we begin to consider how we might engage our learners with this. Perkins offers a set of guiding principles that allow us to transition from presenting topics to toolkits.

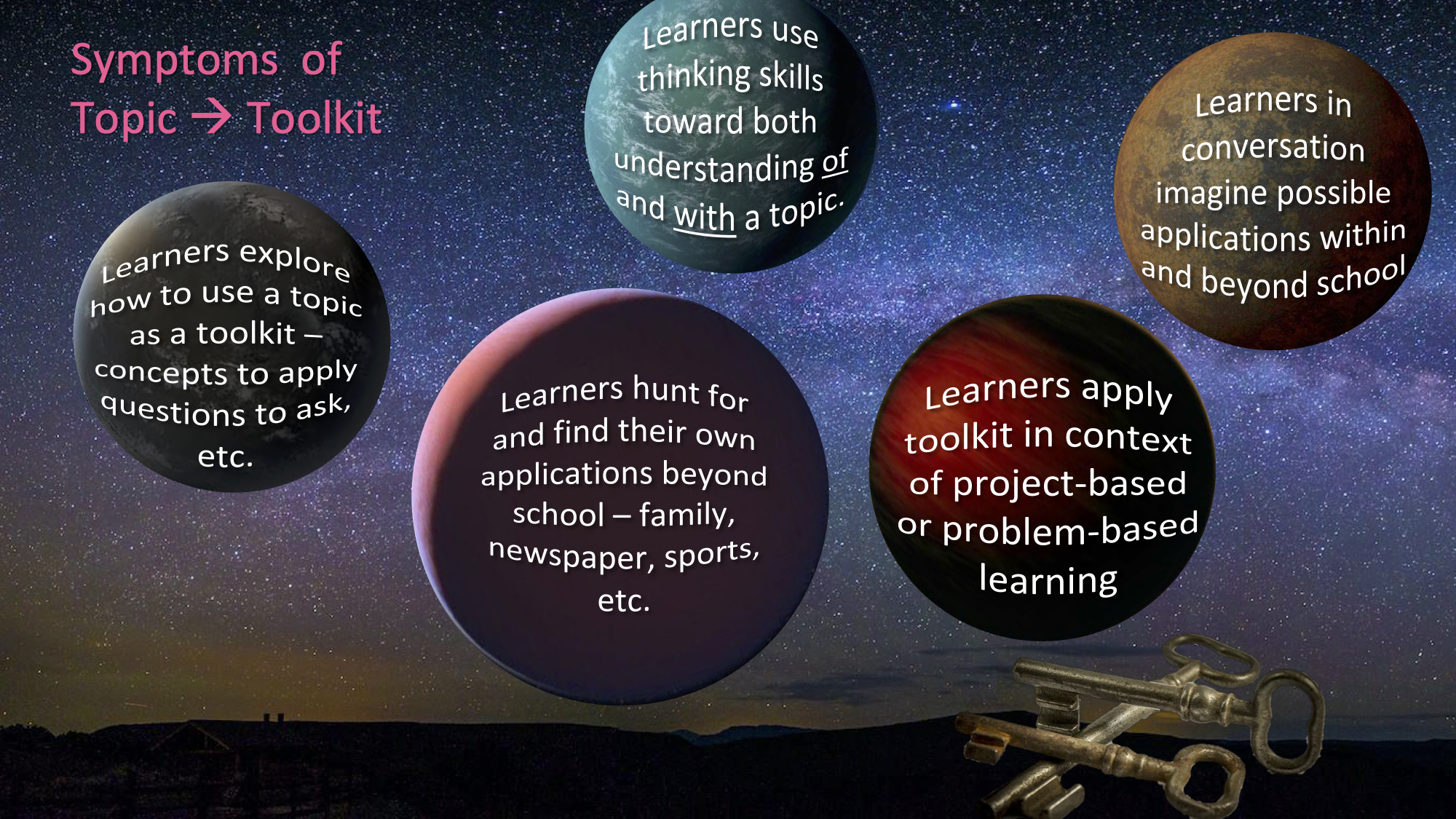

Symptoms of Topic - Toolkit Transition

Learners explore how to use a topic as a toolkit

Learners use thinking skills towards both understanding of and with a topic

Learners in conversation imagine possible applications within and beyond school

Learners apply the toolkit in the context of project-based learning

Learners hunt for and find their own applications beyond school - family, newspaper, sports, etc

There was most certainly a great deal to think about in this webinar, and putting all of this into practice will take time. One of the great skills that Perkins possess, is the ability to weave complex and complicated ideas into a simple narrative. The challenge now is to breathe life into these ideas, to make lifeworthy learning the norm and to overcome the obstacles to this goal.

The ideas in this webinar can be explored further by reading:

Future Wise: Educating our children for a changing world - David Perkins (2014)

Making Learning Whole: How seven principles of teaching can transform education - David Perkins (2010)

By Nigel Coutts

Attenborough, D. “Sir David Attenborough: Climate change our greatest threat” accessed 5.5.19 - https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-46398057

Friedman, T. “Thank you for being late”, Great Britain: Picador, 2016, 461 p.

Harari, Y. “21 Lessons for the 21st Century”, London, Random House, 2018, 416 p.

Sardar, Z. “Welcome to postnormal times”, Futures, 42(5), 2010, p. 435-444.

USAWC. “Origins of VUCA” Accessed online 5.5.19 - http://usawc.libanswers.com/faq/84869